Are EMFs bad? — assessing the evidence, Part I: RF-EMF

- Introduction

- Section I: How do we know if something causes harm?

- Section II: RF-EMF studies

- Section III: Returning to the skeptical arguments

- Section IV: Bradford Hill assessment

- Section V: Beyond carcinogenicity

- Section VI: A wrench, and an odd possibility

- In conclusion

Introduction

The discourse around EMFs (electromagnetic fields) and whether they are harmful to humans is a mess, tainted by poorly-communicated conclusions, bad studies, and more.

And to be fair, it’s a tough thing to pin down. We’re talking about an exposure that:

- went from near-zero for most people to near-constant in the space of just a couple decades for some types of EMF

- where many of the theorized biological effects might only appear decades after exposure begins

- and the general term for which, “EMFs,” refers to the entire electromagnetic spectrum — an enormously varied exposure category

- where it’s nearly impossible to run controlled human trials that keeps participants totally unexposed for long periods of time, even though many of the theorized effects might only appear with chronic use

- plus the details of our exposures have varied massively over the last couple decades as technology has advanced

- and the increase in exposure is tightly coupled to devices and quality-of-life improvements that people most certainly don’t want to give up

- plus, the commercialization of these technologies has been an absolute goldmine for industry, who most certainly don’t want them to be perceived as harmful

If you’re not familiar with what EMFs are from a conceptual / scientific perspective, I’d recommend reading my earlier post, “A rational, skeptical, curious person’s guide to EMFs”. Ideas from that piece will be referenced throughout.

This post series is meant to be a rigorous breakdown of the current state of scientific understanding around the health effects of EMFs.

Or, at least, it’s meant to represent what my understanding of the current state of scientific understanding is. Please do reach out with any thoughts and especially any corrections. I am not a professional scientist. But I’ve tried to reason about this from first principles and examine the evidence honestly and openly.

It is long. I’m sorry. But I’m trying to do right by what is a very complex topic, while also making it a bit readable than most journal articles.

(Although if you want to read it in a printable format that looks more journal-y and less blog-y, here’s a link.)

So, what’s the question?

Asking “are EMFs bad for you?” is not a question that leads to well-bounded, falsifiable conclusions. We need to define what we’re even talking about — what is the specific, testable question we are looking to answer? — something that is often lost in the noise of EMF debates.

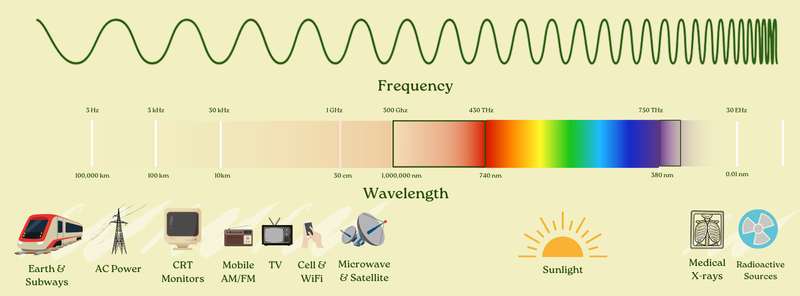

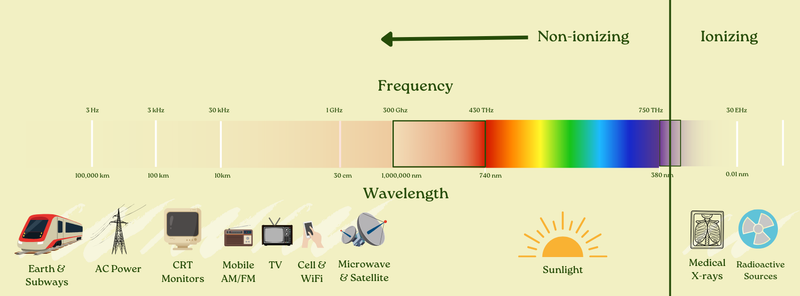

First: the electromagnetic spectrum is wide. Which parts of it are we talking about?

There is no dispute that higher-frequency EMFs like x-rays and gamma rays can cause harm — but they do so through directly breaking chemical bonds. This class of EMFs is called “ionizing radiation” and is known to be harmful through this mechanism. But the ionization capacity of EMFs stops around a roughly 120nm wavelength — or the extreme end of the UV part of the spectrum. To the left of that (longer wavelength) there is not ionization potential.

Moving further down the frequency range from x-rays, there’s also little-to-no dispute that visual light can have biological impacts, including negative ones if used “improperly” — think about blue light disrupting circadian rhythm.

There’s also no dispute that even lower-frequency EMFs can be harmful if they are at high enough power density to cause “thermal effects.” Think about a microwave oven (roughly the same type of EMF as Wi-Fi signals, albeit at much higher power): obviously if you put yourself in a microwave, the result wouldn’t be pretty. That’s because your tissue would actually heat up, which can clearly be damaging.

These undisputed “thermal effects” are the basis for much of the US regulatory regime (the history of which I wrote about here). We are generally protected from these thermal effects by regulation.

So really, what we’re talking about is whether non-ionizing EMFs at power levels too low to cause thermal effects can have deleterious impact on humans.

The place to focus is on the two most controversial and debated common types of exposure:

-

Radiofrequency EMF (RF-EMF): the type of radiation associated with modern wireless communications like WiFi, cell service, and Bluetooth. Frequencies typically range from about 700 MHz to 6 GHz, with 5G extending higher.

-

Extremely Low Frequency Magnetic Fields (ELF-MF): a type of radiation associated with power lines, transformers, and electrical wiring. The core frequency is typically 50-60Hz.

And within these, what is most of interest is exposure at typical levels and durations.

In Part I of this post, I will focus only on RF-EMF. Part II will cover ELF-MF.

We also must consider who it is that we’re talking about. An exposure doesn’t need to negatively impact everyone for it to be considered “bad.” If we were to find out that typical levels of RF-EMF were negatively impacting babies, or immunocompromised people, we’d want to know that — even if it was fine for another chunk of the population.

And so perhaps the precise question to answer is something like: is there reason to believe that RF-EMF, at exposure levels and durations typical in modern life, may cause increased risk of adverse health effects, at least for sensitive members of the population?

Why you probably think this is nonsense

If you’re like most educated people, your prior on “EMFs are harmful” is pretty low. Mine was too. Here’s what my arguments were before I got into the literature:

-

The physics argument: Non-ionizing radiation doesn’t have enough energy to break chemical bonds. It can’t damage DNA the way X-rays do. Basic physics says it shouldn’t matter.

-

The authority argument: The FDA, WHO, and every major health agency says current exposures are safe. These are serious institutions with public health mandates.

-

The mixed results argument: Some studies find effects, others don’t. If EMFs really caused harm, wouldn’t the evidence be more consistent? The positive findings must be cherry-picked.

-

The vibes argument: The people worried about EMFs seem to overlap with extremely-woo, low-rigor crowds. Smart, serious people don’t worry about this stuff.

-

The population argument: Cell phone use went from zero to near-total penetration in a couple decades. If it caused cancer, we’d see a massive spike in brain tumors.

Each of these arguments has something to it, and should be factored into our view of the corpus of evidence. However — to spoil my conclusion — I’ve come to believe that none are a silver bullet that totally proves the case against EMF harm. They should be weighed, but they do not end the discussion.

Bottom line up front

Before I send you down a long (~25,000 word?) rabbithole, I’ll share my bottom line conclusions on the basis of the evidence. Here they are:

The weight of scientific evidence supports that there is reason to believe that RF-EMF, at exposure levels typical in modern life, may increase the risk of adverse health effects.

But also: there is immense uncertainty, and it is not clear how applicable historical studies are to our modern exposure levels given constantly changing characteristics of the exposure profile (this could cut either way — positive or negative).

We are effectively running a uncontrolled experiment on the world population with waves of new technology which have no robust evidence of safety.

If you believe new exposures should be demonstrated to be safe before being rolled out to you, you should take precautions around RF-EMF exposures (which have not been demonstrated to be safe).

If you only believe precautions are warranted for exposures which are demonstrated to be harmful, then perhaps you don’t need to.

To explain how I got to those conclusions, we will:

- Walk through how science actually establishes that something causes harm. This matters because most people have a mistaken model of how this works.

- Go through animal studies, human epidemiological studies, and studies on potential mechanisms, each in detail, with a focus on carcinogenicity (the most-studied potential endpoint for RF-EMF impact).

- Return to the skeptical arguments and address them explicitly

- Evaluate the body of scientific evidence against our proposed criteria for assessing causality of harm.

- Touch on potential non-carcinogenic effects

- And move to our conclusion and overall reflection

Before we go further, a disclosure: I co-founded Lightwork Home Health, a home health assessment company that helps people evaluate their EMF exposure (as well as lighting, air quality, water quality, and more). As such, I have an economic interest in this matter.

With that said, I want to be clear about the causal direction: I co-founded Lightwork after becoming convinced by the evidence of these types of environmental toxicities. That’s why I started the business. This research isn’t a post-hoc way for me to justify Lightwork’s existence!

And regardless, my purpose here to do my best to present the evidence fairly — including the strongest skeptical arguments and what would change my mind — and let you draw your own conclusions.

Section I: How do we know if something causes harm?

The problem with proving causation

Here’s a fundamental challenge: you can’t “prove” causation with 100% certainty in modern observational science.

You can’t run a randomized controlled trial where you assign people to use or not use cell phones for 30 years and see who gets brain cancer. You can’t ethically differentially expose children to power lines and track their leukemia rates. For most environmental exposures, definitive experimental proof in humans is impossible.

So how did we conclude that tobacco causes lung cancer? That asbestos causes mesothelioma? That lead damages children’s brains? None of these had randomized controlled trials in humans either.

The answer is: we use a framework for evaluating causation from imperfect evidence.

The Bradford Hill Criteria

In 1965, epidemiologist Austin Bradford Hill proposed nine criteria (or “viewpoints”) for assessing whether an observed association is likely to be causal. These criteria have become a common framework in environmental and occupational health:

-

Strength: How large is the effect? Larger effects are less likely to be explained by bias or confounding.

-

Consistency: Is the association observed repeatedly in different populations, places, and times?

-

Specificity: Is the exposure associated with specific outcomes, rather than with everything?

-

Temporality: Does exposure precede the outcome?

-

Biological gradient: Is there a dose-response relationship? This need not always be true, but is a factor.

-

Plausibility: Is there a biologically plausible mechanism by which the exposure could cause the effect in question? (although Hill noted our knowledge here may be limited)

-

Coherence: Is there agreement between epidemiological and laboratory findings?

-

Experiment: Do experimental studies support causation? (Hill: “Occasionally it is possible to appeal to experimental evidence,” which is largely true here given the nature of the exposure.)

-

Analogy: Are there similar cause-effect relationships we’ve already accepted?

No single criterion is necessary or sufficient (except temporality is considered necessary). You weigh the totality of evidence across all nine. Hill himself emphasized this:

“None of my nine viewpoints can bring indisputable evidence for or against the cause-and-effect hypothesis… What they can do, with greater or less strength, is to help us make up our minds.”

This is, for example, how we decided smoking causes cancer. Not because any single study was definitive, but because the evidence accumulated across multiple criteria: strong associations, consistent across populations, dose-response relationships, biological plausibility from animal studies, coherence with disease patterns.

These criteria are especially helpful for considering causality for questions that are very hard to measure directly / experimentally. Say, for example, “what are the effects of long-term / lifetime mobile device & WiFi use (i.e. RF-EMF exposure) on humans?”

This is basically an unanswerable question in a direct, experimental, RCT-style way. As mentioned elsewhere, you can’t isolate certain people from RF-EMF exposure their whole life, and expose other roughly-equivalent people, and look at what happens to each group.

RF-EMF exposure is inevitable and omnipresent in the modern world. You could put people in a no-EMF chamber for a day vs. not and measure things, but you can’t directly measure long-term exposure’s effects.

So instead, we use something like the Bradford Hill viewpoints and ask: when we consider observational human studies, direct experimental animal studies, plausibility of biological mechanisms, and other characteristics of knowledge all together… what does it say in aggregate?

I’ll return to these criteria after presenting the EMF evidence.

What “null hypothesis significance testing” actually shows

Most modern scientific studies use a methodology called null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). Understanding what it does — and doesn’t — tell you is also crucial here.

The NHST process:

- Assume “no effect exists” (the null hypothesis)

- Collect data

- Calculate: if no effect existed (i.e. if our assumption — the null hypothesis — was true), how likely would we be to see data this extreme?

- If very unlikely (p < 0.05): “reject the null” and be able to claim we have “statistically significant” evidence that some effect exists

- If not unlikely enough: “fail to reject the null” and say we did “not observe a statistically significant effect”

Here’s the critical part: “not statistically significant” does not mean “no effect exists.”

It means: given our sample size, measurement precision, and study design, we couldn’t rule out that the observed data is consistent with no effect.

I know that sounds a little incoherent and pedantic. But it’s a really, really important point for understanding modern science. If you are looking at a study run with NHST (basically all of them now), there are two possible outcomes:

- The study shows that there is a statistically significant effect

- The study fails to confirm a statistically significant effect

The second point by itself is not strong evidence for no effect existing! Said another way: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

You could have an “absence of evidence” finding for a number of reasons, including:

- There truly is no effect

- The effect exists but is small

- The study was underpowered (too few subjects)

- The exposure assessment was too crude

- The follow-up period was too short

- The study design wasn’t suited to detect this type of effect

NHST was designed to prevent false positives — to stop people from claiming effects that don’t exist. It was not designed to prove safety. It cannot prove safety. That’s not what it does.

So when you read “Study finds no significant link between X and Y,” what the study actually found was: “we couldn’t reject the null hypothesis.” That’s not the same as “we proved X doesn’t cause Y.”

Odds ratios, confidence, and intuition

Throughout this post, I will show the results of NHST studies in a typical format for this topic, for example:

OR 2.22 (1.69–2.92)

What does this mean?

OR stands for Odds Ratio. It is a common way of evaluating increased or decreased risk for disease. An OR of more than 1 means an increased risk over baseline; an OR of 1 means no increased risk; an OR of less than one means decreased risk.

Odds Ratio is actually a little bit tricky to build intuition for. Relative Risk is a related but different metric, but can generally only be calculated with access to the entire population, whereas Odds Ratio can be calculated just by sampling a subset of the population.

More specifically, the Odds Ratio is equal to:

- the ratio of exposed people who got the disease to exposed people who didn’t

- divided by

- the ratio of unexposed people who got the disease to unexposed people who didn’t

For example, if:

- 100 people were exposed to a carcinogen, and 10 of them got cancer

- and 200 people were not exposed to that carcinogen, and 7 of them still got cancer

The OR would be:

For our purposes, you can roughly think of this as a “tripling” of your likelihood of getting cancer if exposed to that carcinogen. That’s not quite precise, and statisticians would be upset with me for saying soThe reason statisticians would be upset is that odds ratios compare odds, not probabilities / risk. These are only roughly equivalent when the probability of the event in question is small, which it is for the cancers we will be talking about. But it can lead to surprises a la Simpson’s Paradox if you try to think about odds ratios as similar to relative risk for events with higher probabilities.. But for rare disease like cancer, this is fine for intuition purposes.

Okay so that’s the OR number. Then, in parentheses, I had — this is the 95% confidence interval (CI). We are saying we are 95% sure that the OR is between 1.69 and 2.92, and the point estimate (typically the maximum-likelihood estimate from a regression) is 2.22. We use a 95% confidence interval because we set p=0.05 per the above commentary on NHST (which is standard).

This then leads to an understanding of “statistical significance.” A result is only considered statistically significant if the 95% CI does not include the null hypothesis. This makes sense intuitively — if we’re 95% sure the result falls in some range, but that range includes “there’s no effect,” we shouldn’t claim that we’re confident there is an effect.

In the case of Odds Ratios, the null hypothesis is 1, because “no effect” means “no increased chance over baseline,” and that’s the definition of an OR of 1.

So that means that if you see a confidence interval that includes 1, the result is not statistically significant, no matter how high the front number is. e.g. if a study reports:

OR 4.75 (0.54–9.12)

That is not a statistically significant finding (1 is in the range 0.54-9.12), despite the fact that it seems to say there’s an OR of 4.75.

On the other hand, if a study reports:

OR 1.33 (1.07-1.66)

That is a statistically significant finding of a 1.33 Odds Ratio (roughly 33% increased risk, with the caveats above), with 95% confidence that the true Odds Ratio is between 1.07 and 1.66.

The more data you have and the cleaner / less biased the data is, the closer your measured OR will get to the true value, and the tighter your CI will get around it. The less good data you have, the wider that confidence interval will be (which of course means it is harder to get to statistical significant, if there is an underlying effect).

Note that positive or negative findings that are not statistically significant can still be useful — especially in the context of meta-analyses, which pool multiple similar studies. If a study just happened to be underpowered to find an effect size, when it is pooled, it could help push the overall finding to significance.

Finally: it’s important to recognize that relative risk and absolute risk are two very different things. When we’re talking about ORs, we’re talking about the odds of getting a disease increasing. If that disease is rare in the first place (like tumors we’ll discuss in this piece), even if you face a moderately increased odds ratio, it’s still rare to get the disease! It’s just less rare than it was before. But it doesn’t automatically turn the rare disease into a common epidemic.

Our roadmap

In the interest of evaluating the Bradford Hill viewpoints, we will first look at animal studies, then human epidemiological studies, and then some proposals on biological mechanisms.

Once we’ve done so, we’ll be able to go through the criteria on the basis of that corpus of evidence and weigh it.

We laid out our principal question earlier:

Is there reason to believe that RF-EMF, at exposure levels and durations typical in modern life, may cause increased risk of adverse health effects, at least for sensitive members of the population?

Like I said, we’ll focus mostly on cancer risk as that is the most studied endpoint. So really, for most of the post we’ll be focusing on:

Is there reason to believe that RF-EMF, at exposure levels and durations typical in modern life, may cause increased risk of cancer, at least for sensitive members of the population?

And we will answer that question by looking at animal studies, epidemiological studies, and biological mechanisms, and then applying the Bradford Hill criteria to that data.

Section II: RF-EMF studies

Animal studies

First, we’ll consider: is there evidence of RF-EMF carcinogenicity in animals at relevant exposure levels? For this question, we don’t need to look very hard.

The National Toxicology Program Study

In 2018, the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP) released results from a $30 million, decade-long study — the most comprehensive, rigorous experimental animal assessment of cell phone radiation ever conductedAlso, I believe the only RF-EMF study the US Government has ever conducted, which feels surprising. They were going to do more after this one but cancelled them with this (pretty odd, in my opinion) reasoning: “The research using this small-scale RFR exposure system was technically challenging and more resource intensive than expected. In addition, this exposure system was designed to study the frequencies and modulations used in 2G and 3G devices, but is not representative of newer technologies such as 4G/4G-LTE, or 5G (which is still not fully defined). Taking these factors into consideration, no further work with this RFR exposure system will be conducted and NIEHS has no further plans to conduct additional RFR exposure studies at this time.” You’d think those factors would make them want more studies… (I discuss what led to this study in an earlier post).

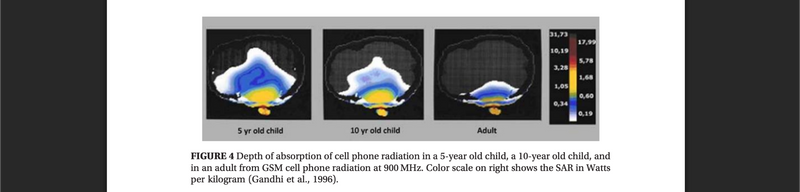

The NTP study exposed rats and mice to cell phone RF-EMF frequencies with common cellular signal modulation schemes (albeit from the early 2000s, since that is when the study was designed). The animals were exposed to levels around and above (although in the same order-of-magnitude) current human limits for 9 hours/day, 7 days/week, for roughly two years (a lifetime for rats). The study was carefully designed, with controlled exposure chambers and sham-exposed concurrent controls.

The NTP uses a standardized evidence scale: “clear evidence,” “some evidence,” “equivocal evidence,” “no evidence.” They found:

- Clear evidence of an association with tumors in the hearts of male rats (malignant schwannomas)

- Some evidence of an association with tumors in the brains of male rats (malignant gliomas)

- Some evidence of an association with tumors in the adrenal glands of male rats (benign, malignant, or complex combined pheochromocytoma)

- Unclear findings if tumors observed in the studies were caused by exposure to RFR in female rats (900 MHz) and male and female mice (1900MHz)

Remember these tumor categories — schwannomas and gliomas — for when we get to the epidemiological evidence.

“Clear evidence” is the highest confidence rating NTP assigns, and is not something they say lightly. Their definition of it is:

Clear evidence of carcinogenic activity is demonstrated by studies that are interpreted as showing a dose-related (i) increase of malignant neoplasms, (ii) increase of a combination of malignant and benign neoplasms, or (iii) marked increase of benign neoplasms if there is an indication from this or other studies of the ability of such tumors to progress to malignancy.

And “Some evidence” is defined as:

Some evidence of carcinogenic activity is demonstrated by studies that are interpreted as showing a test agent-related increased incidence of neoplasms (malignant, benign, or combined) in which the strength of the response is less than that required for clear evidence.

Both of those categories are considered by the NTP to be “positive findings.”

They also published followup papers, including one looking at DNA damage, which found significant increases in DNA damage in:

- the frontal cortex of the brain in male mice

- the blood cells of female mice

- the hippocampus of male rat

The NTP studies are among the strongest experimental signals in the literature, and are rightfully seen as extremely compelling evidence for carcinogenicity (in animals) of RF-EMF at levels on the same order as human exposure. And as they concludeWith a similar paragraph for the CDMA-exposed rats, with slight variations.:

Under the conditions of this 2-year whole-body exposure study, there was clear evidence of carcinogenic activity of GSM- modulated cell phone RFR at 900 MHz in male Hsd:Sprague Dawley® SD® rats based on the incidences of malignant schwannoma of the heart. The incidences of malignant glioma of the brain and benign, malignant, or complex pheochromocytoma (combined) of the adrenal medulla were also related to RFR exposure. The incidences of benign or malignant granular cell tumors of the brain, adenoma or carcinoma (combined) of the prostate gland, adenoma of the pars distalis of the pituitary gland, and pancreatic islet cell adenoma or carcinoma (combined) may have been related to RFR exposure.

The Ramazzini Institute Study

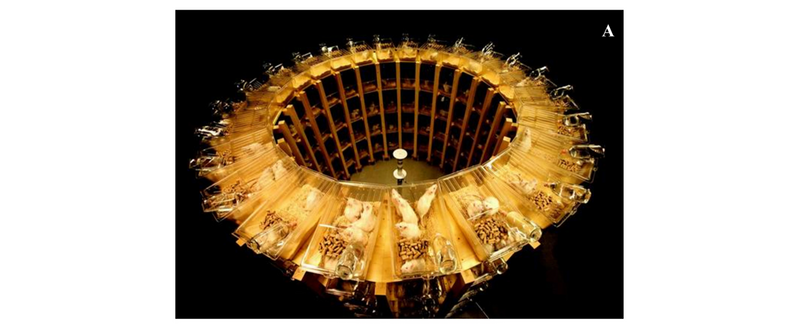

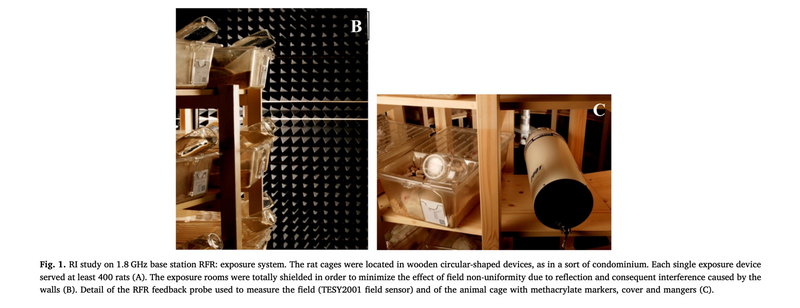

The Ramazzini Institute in Italy — a respected independent toxicology laboratory — then conducted a parallel study examining cell radiation, seeking to reproduce or counter the NTP’s results.

They referred to this setup in a caption in their paper as “wooden circular-shaped devices, as in a sort of condominium,” which made me laugh. Not the sort of condominium I want to live in, whether RF-EMF harm is real or not!

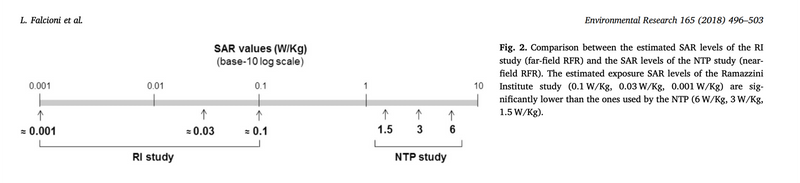

They subjected rats to GSM-modulated RFR at 1.8Ghz over the course of their lives. However, they subjected them to much lower exposures. The NTP exposure was at Specific Absorption Rates (SAR) ranging from 1.5 to 6 W/kg to simulate near-field exposure (like having a cell phone against your head). The Ramazzini exposures were orders of magnitude less, from roughly“Roughly” because the Ramazzini methodology was actually built using a field strength measurement (0, 5, 25, 50 V/m), and converted to SAR estimates via assumptions detailed in section 2.6 of their paper. 0.001 to 0.1 W/kg, to simulate far-field exposure (like being exposed to a cell phone base station or a device further from you).

- A statistically significant increase in the incidence of heart Schwannomas was observed in treated male rats at the highest dose (50 V/m).

- An increase in the incidence of heart Schwann cells hyperplasia was observed in treated male and female rats at the highest dose (50 V/m), although this was not statistically significant.

- An increase in the incidence of malignant glial tumors was observed in treated female rats at the highest dose (50 V/m), although not statistically significant.

And so they conclude:

The RI findings on far field exposure to RFR are consistent with and reinforce the results of the NTP study on near field exposure, as both reported an increase in the incidence of tumors of the brain and heart in RFR-exposed Sprague-Dawley rats.

So, critically — they found at minimum a statistically significant increase in malignant heart schwannomas, which was one of the key findings of the NTP study. And remember that the Ramazzini exposures were 50-1,000 times lower than NTP — within the range people experience simply living near cell towers.

In science, independent replication is everything. When two labs find overlapping unusual results without coordination, it’s very unlikely to be a methodological artifact. And these were two independent, top-tier labs, in different countries, looking at different but adjacent exposures, and finding the same rare tumor types.

Further evidence

There are other studies that suggest other effects from RF-EMF on animals. But for the sake of brevity, I will focus on just findings related to those above (as I believe they have the strongest evidence).

Conveniently, the WHO recently commissioned a systematic review of animal cancer bioassays: Mevissen et al. (2025), Environmental International. The review found that across the 52 publications included, after evaluating for risk of bias, there was evidence that RF-EMF exposure increased the incidence of cancer in experimental animals, with:

- high certainty of evidence for malignant heart schwannomas

- high certainty of evidence for gliomas

This is exactly in line with (and partially driven by) the NTP & Ramazzini findings. I have not seen much dispute over these conclusions.

There are many other animal studies on RF-EMF (including several interesting ones around RF-EMF increasing tumor rates when animals are also exposed to separate known carcinogens).

But because I believe the conclusions above (high certainty of evidence for an association in experimental animals between RF-EMF exposure and gliomas/schwannomas) is relatively uncontroversial, I will leave it here, as this minimum bar is sufficient to make an overall argument. Any additional study inclusion would be for purposes of increasing the scope of potential RF-EMF biological impacts, which we can reserve for a future post.

And brevity is important, because we’re about to get into a more controversial area (which will thus take up much more space): the human studies. So let’s get into those.

Human studies

Now, let’s turn to the human studies on RF-EMF. Unlike rats, we can’t put humans in isolated experimental “wooden circular-shaped condominiums” and blast them with RF-EMF or sham controls for their entire life. So instead, we rely on observational studies — typically either of the case-control variety, or prospective (the differences between which we will discuss shortly).

This difference is why we want to look at both animal and human studies (as well as other evidence): because it is only in concert that we can get a fuller picture.

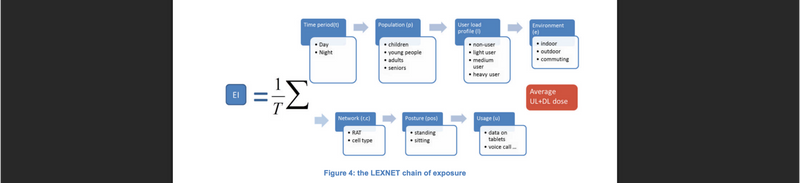

There is also a challenge with RF-EMF in particular, as opposed to many other potential toxins: it is really, really hard to get accurate measurements of exposure. In the animal trials, we could look precisely at a quantified SAR (basically absorbed radiation) or field strength (ambient radiation), because the animals were in isolated, shielded chambers. But human exposure is a whole different beast.

Your phone transmits at variable strengths (fewer bars of signal actually means the phone boosts its radio and outputs higher power!), you move through a varying ambient field all day (are you close to a WiFi router? a cell tower?), and many ways of cutting this rely on some degree of human recall (how long were you on your phone?). Plus: cellular technology is constantly changing, so the same behavior one year may have a totally different exposure profile than the next.

This creates a huge amount of noise and challenge in the data. Studies take different approaches, and we will attempt to look at them individually and in totality. But it is worth bearing these challenges in mind. In general, most studies tend to focus on simply “cell phone usage,” with many studies tracking time spent on calls. Especially at large enough scale, this is perhaps the best way to get at exposure, but still leaves questions and noise.

The INTERPHONE Study

The most noteworthy case-control cell phone study is generally considered to be the INTERPHONE study. The main paper was published in 2010, and there have been a number of followups and country-specific ones as well.

INTERPHONE was coordinated by the WHO’s cancer research arm (IARC), and looked at people across 13 countries. They found tumor cases between 2000-2004 and matched controls from the same populations, giving both detailed interviews about cell phone use history. It involved 2,708 glioma cases and 2,409 meningioma cases.

Their headline finding was that there was no overall association between cell phone use and gliomas or meningiomas (“No elevated OR [Odds Ratio] for glioma or meningioma was observed ≥10 years after first phone use.”). However: when you read the details, a more nuanced picture emerges.

The details

As the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; the organization that kicked off the study) said themselves in 2010 when the study results were announced:

The majority of subjects were not heavy mobile phone users by today’s standards. The median lifetime cumulative call time was around 100 hours, with a median of 2 to 2-1/2 hours of reported use per month. The cut-point for the heaviest 10% of users (1,640 hours lifetime), spread out over 10 years, corresponds to about a half-hour per day.

You may wonder, as I did: for those “heaviest 10% of users” who spend more than 1,640 lifetime hours over 10 years, averaging “about a half-hour per day”… what was their outcome?

You wouldn’t have guessed it from the topline “no elevated odds ratio” conclusion, but:

In the tenth [highest] decile of recalled cumulative call time, ≥1,640 h, the OR was 1.40 (95% CI 1.03-1.89) for glioma

Said another way: there was a statistically-significant 40% increased odds ratio of glioma in this set of “heavy users.”

Even more than that, in this same “heavy usage” group, the OR for temporal lobe (the part of the brain most adjacent to where you hold your phone) glioma was 1.87 (95% CI 1.09–3.22). This means there was a statistically-significant 87% increased risk of temporal lobe gliomas for heavy users over people that were not regular users of their phones (i.e. they used them less than once per week!).

And even more interesting than even that: you might wonder, for this high-usage set, was there a difference in which side of the brain the tumor appeared on? And indeed, there was. Of those with glioma, “ipsilateral” phone use (i.e. mostly holding your phone on the same side of your head as where a tumor developed) came with an OR of 1.96 (95% CI 1.22–3.16) versus “contralateral” phone use (i.e. mostly holding your phone on the opposite side of your head from the tumor) at 1.25 (95% CI 0.64-2.42).

Said another way: there was a strong, statistically significant correlation between which side of their heads the glioma participants held their phone on and which side their tumor was on.

Now most people I know use their mobile phones — on a call or in their hand browsing — maybe 5 hours a day (various online stats agree with that order of magnitude). That’s 150 or so hours a month, or 1,800 hours a year. INTERPHONE considered “heavy users” to be those with more than 1,640 hours of lifetime exposure.

But critically — as we will address later in this piece — holding a phone up to your ear (really the only way people used them in the 90s’ INTERPHONE usage era) is a very different and more intense exposure profile than holding it in your hand. So I’m not suggesting at all that modern usage hours are simply a scaled-up version of the INTERPHONE usage.

In fact, if that were the case, cancer numbers would be off the charts right now — we’ll also discuss this dynamic later.

But the point remains: 1,640 hours of lifetime exposure feels well within reach for a “normal” user today — not just a “heavy” one. And the INTERPHONE study suggests that range has a statistically significant association with glioma, and especially with ipsilateral, temporal lobe glioma.

A reasonable question may arise: am I cherry-picking here? I’m only talking about the highest-usage group (more than 1,640 hours of lifetime cell phone use), when all the lower-usage groups showed much less — or zero, or negative — impact from cell phone usage.

Well: I think that group is especially relevant to our original question. We’re trying to figure out whether “exposure levels and durations typical in modern life” have negative health effects. The highest-usage group in the INTERPHONE study used their phones on average about half an hour a day.

Imagine we were studying whether eating ultra-processed food (UPF) was correlated with obesity, and we found a big, well-run study that looked at food consumption of the following groups over 10 years:

| Group | % of calories from UPF |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | ~0% |

| Group 2 | < 5% |

| Group 3 | < 10% |

| Group 4 | < 15% |

| Group 5 | < 20% |

| Group 6 | ≥ 20% |

And imagine that study found that for Group 6, there was a statistically-significant 40% increased risk of obesity over Group 1, but for Groups 2-5, there was no statistically significant increase. And on that basis, we said “no elevated OR for obesity was observed ≥10 years after first ultra-processed food consumption.”

That’s all well and good, but, uh, ultra-processed food now accounts for nearly 60% of US adult calorie consumption. So most people are way into the top group, and as such, that’s the only one that is particularly relevant to look at.

And that maps almost exactly to what the INTERPHONE study.

To be clear, I don’t blame the INTERPHONE authors. They conducted their study based on cell phone usage at the time — the late 1990s and early 2000s. And in their press release when they released the study, they said:

Dr Christopher Wild, Director of IARC said: “An increased risk of brain cancer is not established from the data from Interphone. However, observations at the highest level of cumulative call time and the changing patterns of mobile phone use since the period studied by Interphone, particularly in young people, mean that further investigation of mobile phone use and brain cancer risk is merited.”

(That quote also hints at our later consideration of “sensitive groups” — INTERPHONE only looked at adults, not children.)

There are other critiques of the study (including shortcoming the investigators themselves highlight, and many others published): it was short latency (most cases had only a few years exposure; brain tumor latency is commonly decades), they found an implausible protective effect at low exposure (OR < 1.0) which signals systematic bias pushing results towards null, there were clearly recall errors and possible selection biases, and more.

Additionally and importantly — this will come up again later in our analysis of the evidence — the INTERPHONE study only looked at cellular phone use as “exposure” but not cordless phone use. At the time the study was done, DECT cordless phones (remember these guys?) were common — and they also emit RF-EMF. But the INTERPHONE study put usage of those devices in the “not exposure” bucket. So when they then compared the “more exposed” groups to the “less exposed” groups, it was not a proper comparison of RF-EMF exposure. The study measured the association of “cellular phone usage” with cancer, but not “RF-EMF exposure” to cancer (and this cordless exclusion statistically biased the study towards the null).

But at the end of the day, when looking at the data (not just the conclusions), I find the INTERPHONE study a persuasive argument in favor of glioma correlation with what might be in the range of typical modern cell phone usage. And that’s even before we look at other epidemiological studies like…

The Hardell Studies

Swedish researcher Lennart Hardell has conducted the a series of studies over two decades. He’s careful to include deceased cases, detailed laterality analyses, long followups (some 25+ years), cordless phone exposure (not just cellular phone), and dose-response analysis.

To take one of his papers as a representative example (Hardell & Carlberg (2025), Pathophysiology, a pooled analysis of two of their studies):

- mobile phone use increased risk of glioma, OR 1.3 (1.1-1.6)

- the OR increased statistically significantly per 100 hours of use, and per year of latency

- high ORs were found for ipsilateral mobile phone use, OR 1.8 (1.4-2.2)

- the highest risk was found for glioma in the temporal lobe

- first use of mobile phone before age of 20 gave higher OR for glioma than in later age group

There are several other Hardell studies that find similar results. We’ll cover their aggregate outcomes in the meta-analyses section below.

The laterality finding is crucial to addressing a possible source of bias (both here and in the INTERPHONE study). If recall bias drove these results — people with tumors overreporting phone use — they’d likely end up overreporting on both sides. There’s no reason to misremember which ear you used.

But increased risk appears specifically on the side where phones were held. That’s exactly what you’d expect from a true biological effect, and is strongly suggestive of a lack of bias (although there remain possibilities around differential recall of side, post-diagnosis rationalization, etc.).

With that said, Hardell’s studies are often contested. His work consistently finds larger effects than other research groups, which is a clear driver of scrutiny.

He has also done a lot of studies (more than anyone else on this topic), and depending on your view on the matter, this ends up biasing meta-analyses (which we’ll cover in a moment) one way or the other. Either Hardell’s studies are included in the meta-analysis, which drives the association between RF-EMF and cancer up, or they are excluded, which weakens the association substantially — or even eliminates it.

Critics point to several concerns, most of all his effect sizes not being replicated by other major studies (i.e. an elevated association found in a study is correlated with that study being performed by Hardell). These concerns should be taken into account when weighing the evidence.

It’s worth noting that the INTERPHONE study (commonly cited as a disagreeing result from Hardell) is actually more in line with his findings than people give it credit for, per my argument above. And I will address some of the other major studies (Million Women; Danish cohort) momentarily.

There was also a noteworthy rebuttal to Hardell in Little et al. (2012), BMJ, which argued that the observed 2008 glioma rate in the US did not line up with what Hardell’s risk estimates would have predicted. I mention this rebuttal in particular (there are many!) because, as I will address later, this and related ideas are what I find to be the most persuasive line of argument against an association between common levels of mobile phone use and cancer.

Little’s paper led to a flurry of replies (Kundi, Davis, Hardell himself, and Little et al. about the methods used. It is a complicated topic with no black-and-white answer, and worth reading the full series of letters if you are interested.

However, even if were to accept Little’s work at face value and thus that Hardell’s work overestimates the association (although I haven’t seen a compelling methodological argument for why that might be the case): the Little paper still finds that using the INTERPHONE risk estimates — including the elevated odds ratio in the highest-use bins — the projected glioma rate is in line with the observed rate.

And, similarly to my observations on the INTERPHONE study, I can believe two things at the same time: 1) that the work was performed properly, and 2) that it simply does not reflect the reality of modern RF-EMF exposure.

More precisely: the Little study did not have access to actual cell phone usage data in the US, so they assumed it matched the usage of the INTERPHONE control group (which I think is a reasonable assumption, given the constraints). And, depending on the “latency period” you are looking at in the INTERPHONE study, the percentage of people who had more than 1,640 total lifetime hours of mobile phone use was relatively small, which means, coupled with a moderate effect size, there would be very limited projected increase in glioma incidence. And again, that is perhaps a fair annual count of usage for modern exposure.

Little assessed mobile phone subscriptions from 1982 onwards, for evaluation of glioma incidence from 1992 to 2008. This was important work, but does not reflect modern usage. Even if we assume all the work was done correctly, it’s still looking at exposure levels a fraction of what we face today.

And if you build in their assumed latency of 10+ years for tumor incidence and the possibility — reflected by INTERPHONE’s conservative findings — that low usage (<1,640 lifetime hours) doesn’t create a large effect size but usage above that creates a moderate effect, it is entirely coherent to suggest that INTERPHONE and Little’s findings are correct and we are facing the possibility that modern exposures are on track to produce increased incidences.

Million Women & Danish cohort

In contrast to findings above, there are two large-scale studies that are often cited as counterpoints (well, actually — INTERPHONE is typically cited as a negative finding, but per my analysis above I consider it a positive one!): the Million Women Study in the UK, and the Danish cohort study.

The Million Women Study is a very impressive large-scale project. 1.3 million UK women were recruited and followed for health outcomes. This has resulted in a huge array of papers. The study was not specifically focused on RF-EMF (or focused on anything specific, really — it was meant to provide large data across many facets to be later evaluated). But papers on cellular phone exposure were produced, including Schüz et al. (2022), J Natl Cancer Inst.. The core finding:

Adjusted relative risks for ever vs never cellular telephone use were 0.97 (95% confidence interval = 0.90 to 1.04) for all brain tumors, 0.89 (95% confidence interval = 0.80 to 0.99) for glioma, and not statistically significantly different to 1.0 for meningioma, pituitary tumors, and acoustic neuroma. Compared with never-users, no statistically significant associations were found, overall or by tumor subtype, for daily cellular telephone use or for having used cellular telephones for at least 10 years.

So: no association found. However (emphasis mine):

In INTERPHONE, a modest positive association was seen between glioma risk and the heaviest (top decile of) cellular telephone use (odds ratio = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.89). This specific group of cellular telephone users is estimated to represent not more than 3% of the women in our study, so that overall, the results of the 2 studies are not in contradiction

There are, as usual a variety of letters and rebuttals (Moskowitz, Birnbaum et al., Schüz). I find arguments on various points persuasive on both sides in terms of methodological strengths and weaknessesI also note that those opposed to the “no association” conclusions are not cranks — for example, Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D. was director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Toxicology Program (NTP) from 2009 to 2019, and before that spent 19 years at the EPA where she directed the largest division focusing on environmental health research. Her co-author on the letter is Hugh Taylor, MD, chair of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at Yale..

But for me, the piece that really matters — as in my breakdown of the INTERPHONE study — is this “heavy user” question, which today is much closer to “typical use.” It is completely plausible that, given the <3% “heavy users” in the Million Women Study, an association was not observed even if there is an association between “heavy use” (as defined here) and cancer — and that heavy use population was not broken out in the Million Women paper anyway.

Finding no association for the roughly 97% of women who hadn’t used a cell phone for 1,640 cumulative hours is valuable science. But it is of questionable value in answering our original question. In fact, the study authors themselves, in their reply letter, say:

We do agree, however, with both Moskowitz and Birnbaum et al. that our study does not include many heavy users of cellular phones. This study reflects the typical patterns of use by middle-aged women in the UK starting in the early 2000s.

…

Overall, our findings and those from other studies support our carefully worded conclusion that “cellular telephone use under usual conditions [Schüz et al.’s emphasis] does not increase brain tumor incidence.” However, advising heavy users on how to reduce unnecessary exposures remains a good precautionary approach.

And so I repeat here: their view of “usual conditions” may or may not be in line with modern RF-EMF usage; and their suggestion that “advising heavy users on how to reduce unnecessary exposures remains a good precautionary approach” is a suggestion that by their own definitions, should likely apply to most people today. Even many of these “negative finding” studies seem to actually suggest such.

The Danish cohort study (Frei et al. (2011), BMJ, among other papers) is another oft-cited study. It looked at Danish cell phone subscribers in the early 1990s and followed up regarding their cancer status between 1990-2007. They found no statistically-significant increased risk for brain / central nervous system tumors.

But this study falls victim to some of the same issues as the prior ones: there are a few methodological weaknesses, but it also fails to address what was then heavy usage but is now typical.

The Danish study did not measure actual exposure / usage. Instead, they simply looked at the binary of whether the individual had a cellular subscription or not, so there was no way to stratify by usage.

But beyond that:

- They excluded corporate subscribers from the “exposed” group and put them in the “unexposed” group unless they also had a personal subscription. There were 200,507 corporate subscriptions out of 723,421 total mobile phone subscription records. I suspect that corporate subscribers may have been the most active users, so this feels like a painful possible misclassification.

- They only had data on mobile phone subscriptions until 1995, so individuals with a subscription starting 1996 or later were classified as non-users / unexposed.

- Once again, cordless / DECT phone users were treated as “unexposed”

- And perhaps most importantly, “the weekly average length of outgoing calls was 23 minutes for subscribers in 1987-95 and 17 minutes in 1996-2002”

So, again: another study that does not feel not strongly informative about the tail of exposure most relevant today.

COSMOS

The most recent large-scale study is the Cohort Study on Mobile Phone Use and Health, or COSMOS, which remains in-progress (Feychting et al. 2024, Environ Int. is the most recent relevant follow-up, but there will be more).

COSMOS is a prospective cohort study following 250,000 mobile phone users recruited between 2007-2012 in several counties across Europe. The headline finding (at least of the 2024 paper) is no association between mobile phone use and risk of glioma, meningioma, or acoustic neuroma.

COSMOS is very interesting, and I will be tracking it closely. It was designed specifically to account for shortcomings in the earlier studies I mentioned. Most of all, the two most relevant and specific earlier study series (INTERPHONE & Hardell’s) were case-control studies — meaning roughly that researchers found people with cancer, then found matching controls, and then asked them all about their cell phone usage.

Whereas COSMOS is a prospective study, which means that they simply started following a population, and will note both cell phone usage over time as well as cancer diagnoses. The intention here is to address what is referred to as “recall bias.” The concern is that people diagnosed with brain tumors, searching for explanations, might unconsciously overestimate their historical phone useThere is evidence for this type of bias. The COSMOS paper cites Bouaoun et al. (2024), Epidemiology, although it’s worth noting that paper shares an author with the COSMOS paper itself. Bouaoun et al. is a simulation study that found a larger variance in reporting errors among INTERPHONE’s cases than its controls..

There are trade-offs between prospective and case-control studies. While the prospective ones reduce recall bias, they also can struggle evaluating rare outcomes, especially those with long latency. You need really big populations, long follow-ups, and you risk exposure classification degrading as technology changes. Case-control studies can capture longer latencies and rare outcomes by design, but that comes with recall bias concerns.

COSMOS also worked to address the “heavy user” question. Their conclusions thus far into the study (median followup of 7.12 years) are that there is no statistically significant finding associating cellular phone use with the cancers they are examining.

Unfortunately (for science and for the study authors), by 2007 — when recruitment began — cell phones were basically everywhere, as were other RF exposure sources like WiFi. So it’s now nearly impossible to have an “unexposed” group to compare to. COSMOS’ approach is to treat the bottom 50% of users (by whatever metric they are slicing for the specific analysis) as the “low exposure” group, and have the 50-75% quartile and 75-100% quartile (and in some cases, the 90-100% decile) as the exposure groups to evaluate against the low exposure group.

This obviously raises the possibility that if even people in the “low exposure” groups are being affected, that could reduce the measured impact on the higher exposure groups and bias towards the null. It’s a limitation of the reality of mobile phone proliferation, but there is a reasonable argument that it would be more appropriate to set the cutoff for “low exposure” much lower than 50%. For instance, I’d be interested in the statistics comparing the bottom decile to the top decile or quartile.

The COSMOS study — as it stands today — has somewhat limited statistical power (especially for certain tumor types like acoustic neuroma), and also is limited by the followup duration (roughly 7 years)Although this should not be confused with the duration of phone usage — the followup duration refers to the time between registration and followup. The participants may have been using mobile phones long before that, and many were. They reported this when they were recruited.. There are only 149 glioma, 89 meningioma, and 29 incident cases of acoustic neuroma. These limitations are not a failure of the study design — simply a commentary on the fact that it is early on. Future followups in the study will help to address these.

It would also be great if COSMOS could report on the laterality of the tumors, as well as their locations. From my perspective, the laterality findings in earlier studies are some of the most compelling pieces of evidence against recall bias, and are a key part of the evidentiary puzzle (although it is also argued variously that these can be subject to their own recall biases). In the first COSMOS paper, laterality and location are not mentioned.

Overall, I find the COSMOS study to be a very thoughtfully-designed approach, with compelling early findings of no association between mobile phone use and the cancers they are looking at. There are limitations, as with every study, but they address them well. I will be watching them closely for followups. This study is one of two places — along with population cancer trends — that I think has the strongest chance of causing me to update my conclusions on this matter (depending on what happens).

But — despite all of that — we must remember what we outlined at the outset. Absence of evidence of an association is not evidence of absence. We need to consider this within the mix of everything else. There is no such thing as a single study “disproving” an effect with certainty. It could be that there is no effect — but it could also be that the study is underpowered for the effect size, the followup period was too short, there was noise, or otherwise.

A final note on COSMOS: after it was published, a group called ICBE-EMF (International Commission on the Biological Effects of Electromagnetic Fields — some of the same dissenters cited in previous episodes) published a methodological critique calling for retraction of the study’s conclusions. The COSMOS authors published a rebuttal. To my eyes, the ICBE-EMF critique raises some valid methodological concerns (some of which I have referenced above), but in this case the call for retraction is too strong. The COSMOS rebuttal defends most of the core points. Both sides have potential biases and perspectives. Net of everything, I find the COSMOS conclusions to be fair based on their data, and think their methodology is a reasonable one. At the same time, I remain deeply grateful for the ICBE-EMF’s work — they tirelessly represent the less-common side of the debate in public and scientific discourse and frequently point out major errors in papers which this post references.

Meta-analyses & reviews

We’ve now gone through several of the biggest / most noteworthy human studies (although there are others!) on the association between cell phone use and cancer. And as you can see, at least from my perspective, the topline conclusions do not always line up with the most relevant takeaway for our purposes today: assessing the impact of typical usage patterns.

This then naturally carries through the meta-analyses. As you can imagine based on the above, if we simply look at a question like “across all these studies, is there an observed association between people who have used cell phones and cancer rates?” the answer will be “no.” But that may miss the detailed conclusions around what was considered “heavy usage” in the early 2000s, or other nuances.

The meta-analyses are all (basically) drawing from the same pool of possible studies. Each then chooses a different set of parameters (inclusion criteria; choices around exposure contrast, latency, laterality, reference group definition; and synthesis approach). These choices impact what question the analysis is answering. I’ve laid what I consider to be the top meta-analyses below, grouped by a couple levers and choices that most meaningfully determine their outcomes.

The latest WHO-commissioned systematic review, Karipidis et al. (2024), Environ Int., concludes, among other findings:

For near field RF-EMF exposure to the head from mobile phone use, there was moderate certainty evidence that it likely does not increase the risk of glioma, meningioma, acoustic neuroma, pituitary tumours, and salivary gland tumours in adults, or of paediatric brain tumours.

As usual, there is an ICBE-EMF critique and a rebuttal. Each make compelling points.

There are then several meta-analyses that effectively come to the conclusion that general usage is not associated with increased risk, but long-term / heavy use (and ipsilateral use) is:

Myung et al. (2009), Journal of Clinical Oncology:

- Overall use: OR 0.98 (0.89–1.07) (null).

- ≥10 years of use: OR 1.18 (1.04–1.34)

- they also note, interestingly, that: “a significant positive association (harmful effect) was observed in a random-effects meta-analysis of eight studies using blinding, whereas a significant negative association (protective effect) was observed in a fixed-effects meta-analysis of 15 studies not using blinding”

Prasad et al. (2017), Neurological Sciences:

- Overall use: OR 1.03 (0.92–1.14) (null)

- ≥10 years of use (or >1,640 hours of use): OR 1.33 (1.07-1.66)

- they add a similar note to Myung et al.: “studies with higher quality showed a trend towards high risk of brain tumour, while lower quality showed a trend towards lower risk/protection.”

- Overall use: OR 0.98 (0.88–1.10) (null)

- ≥10 years of use: OR 1.44 (1.08–1.91)

- Long-term ipsilateral use: OR 1.46 (1.12–1.92)

- Long-term use association with low-grade glioma: OR 2.22 (1.69–2.92)

- Long-term use association with high-grade glioma: OR 0.81 (0.72–0.92) (protective finding)

Moon et al. (2024), Environmental Health:

- Ipsilateral use: OR 1.40 (1.21-1.62)

- ≥10 years of use: OR 1.27 (1.08-1.48)

- ≥896 hours of cumulative use: OR 1.59 (1.25-2.02)

An interesting meta-analysis was performed by Choi et al. (2020), Int J Environ Res Public Health (note that there is author overlap with ICBE-EMF membership). They sought to break down some of the variance in results shown above. A key finding:

In the subgroup meta-analysis by research group, cellular phone use was associated with marginally increased tumor risk in the Hardell studies (OR, 1.15 (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.33; n = 10; I2 = 40.1%), whereas it was associated with decreased tumor risk in the INTERPHONE studies (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.88; n = 9; I2 = 1.3%). In the studies conducted by other groups, there was no statistically significant association between the cellular phone use and tumor risk (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.13; n = 17; I2 = 8.1%).

That is: if meta-analyses include the Hardell studies (of which Choi looked at 10), that will shift them towards finding an association. If they include the INTERPHONE studies (9 of them), that will shift them towards the null (in fact, they show a protective effect). Non-Hardell, non-INTERPHONE studies (17 of them), pooled, show null.

However, Choi et al. also looked at duration and found that for users with >1,000 hours of lifetime call time:

- all studies pooled (Hardell, INTERPHONE, other): OR 1.60 (1.12-2.30) (statistically significant positive finding)

- Hardell: OR 3.65 (1.69-7.85) (statistically significant positive finding)

- INTERPHONE: OR 1.25 (0.96-1.62) (positive finding, but just missed on statistical significance)

- other: OR 1.73 (0.66-4.48) (positive finding, but not close to statistical significance — wide range)

So: what’s the takeaway from all these meta-analyses? At a high level: that the evidence is heterogeneous; that there doesn’t seem to be an association between general phone use and cancer, but that there may be one with longer-term and especially ipsilateral use. Those conclusions are contested, and the literature continues to evolve.

But you may be looking at the very-rigorous Karipidis paper and wondering something like “their general use findings are roughly in line with these other analyses, but their duration/intensity findings aren’t. Why is that?” Karipidis did look at cumulative call time and number of calls in some cases, and reported that they didn’t see a consistent upward trend in those strata.

An important piece of context is that Karipidis et al. isn’t a meta-analysis. For a variety of reasons they did not feel comfortable performing a pooled meta-analysis and instead chose to do a systematic review with risk-of-bias / GRADE scoring to come to conclusions on certainty of evidenceA meta-analysis is a sort of quantitative “pooling” of several studies; a systematic review is a more quantiative-qualitive blended analysis of them, although still procedural and sometimes including subgroup meta-analyses.. So it is also just a different approach to looking at the data than the meta-analyses are.

So the difference arises from a couple places, including their inclusion of cohort studies, not just case-control ones (as in the meta-analyses) and their RoB and evidence certainty scoring. But really, the heart of the disagreement, at least as I read it, is here (emphasis mine):

Consistently with the published protocol, our final conclusions were formulated separately for each exposure-outcome combination, and primarily based on the line of evidence with the highest confidence, taking into account the ranking of RF sources by exposure level as inferred from dosimetric studies, and the external coherence with findings from time-trend simulation studies (limited to glioma in relation to mobile phone use).

In plainer English: Karipidis et al. (per their protocol design) evaluated how reasonable they think the outcomes of studies are before considering how to incorporate them into the evidence output. This is unlike the meta-analyses of case-control studies, which set inclusion/exclusion criteria and then quantitatively pool the results from the included studies. This leads to a wide gap in the findings. It’s hard for me to trace the math exactly, but I believe the biggest impact comes here (emphasis mine):

Three of these simulation studies consistently reported that RR estimates > 1.5 with a 10+ years induction period were definitely implausible, and could be used to set a “credibility benchmark”. In the sensitivity meta-analyses of glioma risk in the upper category of TSS excluding five studies reporting implausible effect sizes, we observed strong reductions in both the mRR [mRR of 0.95 (95 % CI = 0.86–1.05)], and the degree of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 3.6 %).

That is: Karipidis looked at simulation studies, which projected cancer rates and compared to actual numbers from cancer registries. Those studies suggested that relative risk estimates of 1.5 with 10+ year induction periods were “definitely implausible,” and based on that, Karipidis excluded from the sensitivity analyses of glioma risk the five studies that reported effect sizes above that number. This effectively cut out any data that suggested meaningful effects, and as such, significantly pushed their conclusions towards “no effect.”

This is similar to the approach noted in Röösli et al., 2019, Annual Review of Public Health, another skeptical analysis (also not a straightforward meta-analysis):

For glioma and acoustic neuroma, the results are heterogeneous, with few case-control studies reporting substantially increased risks. However, these elevated risks are not coherent with observed incidence time trends, which are considered informative for this specific topic owing to the steep increase in MP use, the availability of virtually complete cancer registry data from many countries, and the limited number of known competing environmental risk factors. In conclusion, epidemiological studies do not suggest increased brain or salivary gland tumor risk with MP use, although some uncertainty remains regarding long latency periods (>15 years), rare brain tumor subtypes, and MP usage during childhood.

I think these are reasonable choices, and both those papers are valuable contributions to the literature. However: I am personally most interested in doing my own evaluation of what is plausible and what is not (that’s the purpose of this post!). I agree with Karipidis and Röösli (et al.) that population-level cancer rates is one of the most compelling arguments against there being an association with mobile phone use and cancer — but I would prefer to address that argument separately (which I will) rather than removing actual data from consideration because of it. Said another way: I want to take that argument as its own stage, rather than using it to cut out data.

So, basically, as I read it, the net of all these analyses is something like this:

- there is broad agreement from both meta-analyses and systematic reviews that simply using mobile phones is not associated with cancer risk

- but pooled meta-analyses tend to show a statistically significant association between heavy usage and/or ipsilateral usage and increased brain cancer risk

- the inclusion or exclusion of Hardell’s studies (moves towards positive) or the INTERPHONE studies (moves towards protective / null) can meaningfully shift the conclusions

- high-profile systematic reviews have chosen to exclude positive findings due to perceived incoherence with population-level trends

So: take from that what you will.

A note on tumor concordance

As noted at the outset of this piece, we are trying to figure out whether there is coherent, consistent evidence that, summed up, points to a high likelihood of risk. One place you would look for that is in similarities between tumor characteristics in the different types of studies.

If you recall from the NTP and Ramazzini animal studies above, the tumors they found were schwannomas and gliomas. Schwannomas arise from Schwann cells (the cells forming myelin sheaths around nerves). Gliomas arise from glial cells in the brain.

These are the exact same cell types implicated in human studies:

- Acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas) — tumors of the hearing nerve

- Gliomas — the most common malignant brain tumor

The animal studies found heart schwannomas as opposed to vestibular ones — although this isn’t necessarily surprising, since the animal studies used full-body radiation rather than the narrower “phone to head” radiation of the epidemiological studies. But it’s the same cell type. And the gliomas overlap directly.

Finding the same rare tumor types in the tissues where the radiation was delivered, between controlled animal experiments and large-scale observational studies, is very strong evidence.

Biological plausibility

Now that we’ve looked at animal and human studies on the carcinogenicity of RF-EMF, we can turn to studies and proposals on the biological mechanisms that may lead to cancer.

This is, of course, tricky. Cancer is a multistage process. You can contribute to carcinogenesis lots of different ways — oxidative stress, disrupted cell signaling, impaired DNA repair, chronic inflammation, or otherwise.

Often when this topic is brought up, people take up the physics argument that non-ionizing radiation lacks the energy to break chemical bonds, which means that this sort of RF-EMF we are examining can’t do direct DNA damage via ionization (which would be an obvious carcinogenic path). This is true.

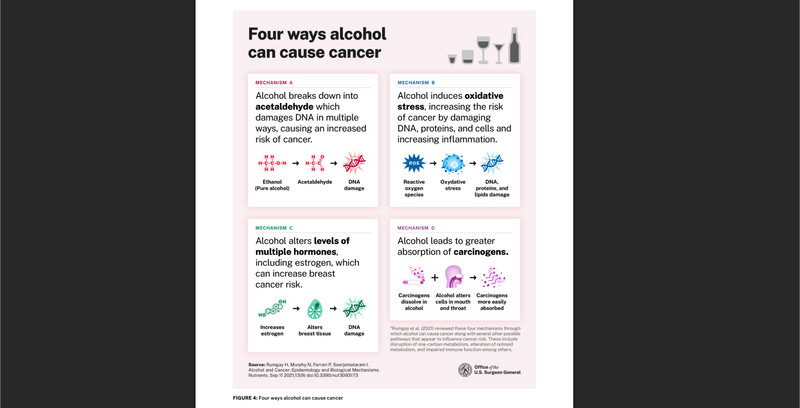

But there are of course plenty of established carcinogens that don’t work through direct ionization. Here is, for example, a page from a U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Alcohol and Cancer risk:

Alcohol can cause cancel through breaking down acetaldehyde, through inducing oxidative stress, through endocrine disruption, and through amplifying the effects of other carcinogens. Plus even more pathways are proposed in the cited paper (Rumgay et al. (2021), Nutrients).

It is common for carcinogenic substances to have multiple pathways that contribute to cancer risk. This may also be the case with RF-EMF. Here we’ll review a few of the plausible mechanisms by which RF-EMF may affect human biology and physiology.

Note that — at least as we’re approaching the topic in this post — these arguments need not draw a straight line all the way through clear impacts on cancer risk to be relevant. The more clear, the better, but under our Bradford Hill criteria, it is simply useful for us to understand evidence for biological outcomes that may lead to carcinogenesis to support the potential causality.

Oxidative stress

There are a lot of studies that have been run, both in vivo and in vitro, on the impact of RF-EMF on oxidative stress markers. In general, my view is that when looking at a mechanism like this, because we are seeking an effect that can be reasonably generalized (or generally rejected) to apply to our Bradford Hill criteria of causality evaluation, it is best to look at the corpus in aggregate rather than point at individual studies.

This differs at some level from the carcinogenicity studies, where we of course want to look at the full set of evidence as context, but it is also highly informative to examine individual studies which show the “full cycle” (exposure to investigated outcome of cancer).

Unfortunately, the two most-cited reviews I have found looking at RF-EMF’s impact on oxidative stress each have flaws that make them unhelpful to rely on fully (don’t worry, we’ll still get to a conclusion). Each one leans a different way.

As part of their recent series of RF-EMF reviews, the WHO commissioned one on oxidative stress, Meyer et al. (2024), Environ Int.. The findings were effectively equivocal:

The evidence on the relation between the exposure to RF-EMF and biomarkers of oxidative stress was of very low certainty, because a majority of the included studies were rated with a high RoB level and provided high heterogeneity

They don’t come to any conclusions with anything beyond “low certainty,” citing high risk-of-bias and high heterogeneity between the studies. There have been many studies — why could they not get to certainty? On this front, I find the ICBE-EMF group’s critique of the paper very compelling (Melnick et al. (2025), Environ Health). Here are some excerpts (although I suggest reading the whole critique if you are interestedNote that I don’t endorse all the perspectives in this paper, which is a critique of all 12 of the WHO’s recent systematic reviews on RF-EMF, cited throughout this post. Also note that Melnick led the design of the NTP cell phone carcinogenicity study discussed earlier during his 28 year NIH / NTP tenure., in addition to the original paper of course):

Much of this discrepancy is due to the excessive exclusion of relevant studies in SR9. Of the 897 articles that Meyer et al. considered eligible for their review, only 52 were included in their MAs; 360 studies were excluded because the only biomarker reported in those articles was claimed to be an invalid measure of oxidative stress

…

Meyer et al. excluded studies in which TBARS [Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances] was reported as the sole measure of oxidative stress because according to Henschenmacher et al., non-oxidative stress reactions including metabolism can also produce TBARS. However, there is no evidence that exposure to RF-EMF activates metabolic pathways that can produce TBARS.

…

Another exclusion criterion for this SR that resulted in exclusion of 63 studies was ”no sufficient exposure contrast”; the external electric field strength (E) field must be greater than 1 V/m or the power flux density (PD) must be greater than 2.5 mW/m2. However, when exposure to RF-EMF produces a statistically significant increase in a biomarker (including increase in 8-OHdG) in exposed vs. sham samples, and those effects are reduced in the presence of an inhibitor of oxidative damage, then such changes represent meaningful RF-EMF-induced oxidative effects.

…

They go on, discussing the exclusion of studies in non-mammalian animal species, the exclusion of studies with mobile phones where output power wasn’t reported, the exlusion of studies where DCFDH was used as the biomarker, and more, summarizing:

Due to the exclusion of studies relevant to the objective of SR9, we conclude that the authors’ conclusions are severely deficient and unreliable.

So — in echoes of the WHO review on the human carcinogenicity studies discussed above — the inclusion/exclusion criteria for analysis for this paper are disputed. And of course, if you cut out large chunks of the relevant studies, you may end up with lower certainty results.

But there is also a second problem with the oxidative stress systematic review: the authors ended up with just 52 studies (after excluding those above — 360 studies were excluded because the biomarker reported was claimed to be an invalid measure of oxidative stress). But then, for analysis, the authors divided the 52 studies into 19 subgroups which were each quantitatively analyzed.

Once you get down to groups that small (just a couple studies per group), of course you are going to end up with low certainty evidence. As the ICBE-EMF group says (emphasis mine):

Indicators of oxidative stress may occur in all organs of all animal species, and are not necessarily specific to only the brain, liver, blood, testis, or ovary of exposed rodents or rabbits, nor is it specific to only in vivo or in vitro studies, and most certainly it is not specific to measurements of only oxidized DNA bases, oxidized lipids, or certain modified proteins or amino acids. Subdividing the 52 primary studies into 19 subgroups resulted in very few studies in most categories; this diluted the overall effect and weakened the significance of the [meta-analyses] reported by the authors of SR9.

The authors here don’t claim that that RF-EMF does not cause oxidative stress — they simply say there is low certainty of evidence, along with some weak suggestions in each direction (maybe yes for oxidative stress in testes, serum, and thymus; maybe no for brain, liver, blood, etc.).

Also, despite all of this, there are several findings in the paper that report statistically significant impacts, even given the authors’ definitions and criteria. These then get rolled into overall “low certainty” total evidence assessments, but the findings stand, includingNote that these are Standardized Mean Differences, not Odds Ratios, so null is 0 not 1. Anything more than 0 is a positive finding (rather than more than 1, as in the OR measures), and statistical significance is when the parenthetical 95% CI range is also all greater than 0 rather than greater than 1.:

- modified proteins and amino acids in the liver of rodents: SMD 0.55 (0.06-1.05)

- oxidized DNA bases in plasma of rodents: SMD 2.55 (1.27-3.24) — they consider this a large effect

- oxidied DNA bases in testes of rodents: SMD 1.60 (0.62-2.59), another large effect

Going the other direction, we have Yakymenko et al. (2015), Electromagn Biol Med, whose conclusions are often cited as the key evidence for oxidative stress:

Analysis of the currently available peer-reviewed scientific literature… indicates that among 100 currently available peer-reviewed studies dealing with oxidative effects of low-intensity RFR, in general, 93 confirmed that RFR induces oxidative effects in biological systems