The Toxic Progress Paradox

Progress is Good. (but sometimes toxic — more on that in a moment.)

In the last hundred years, we’ve invented the internet, nuclear power, DNA sequencing, the laser, GPS, MRIs, integrated circuits, plus compounds and materials like Pencillin, Metformin, graphene, Kevlar, Inconel, aerogels, and reinforced carbon-carbon that have unlocked tremendous advances in medicine and technology.

These inventions and discoveries power the engine of progress. And, broadly, since the pace of progress began accelerating with the industrial revolution, global standards of living have soared.See the Human Progress datasets from the Cato Institute, or Our World in Data.

Just how much are we inventing?

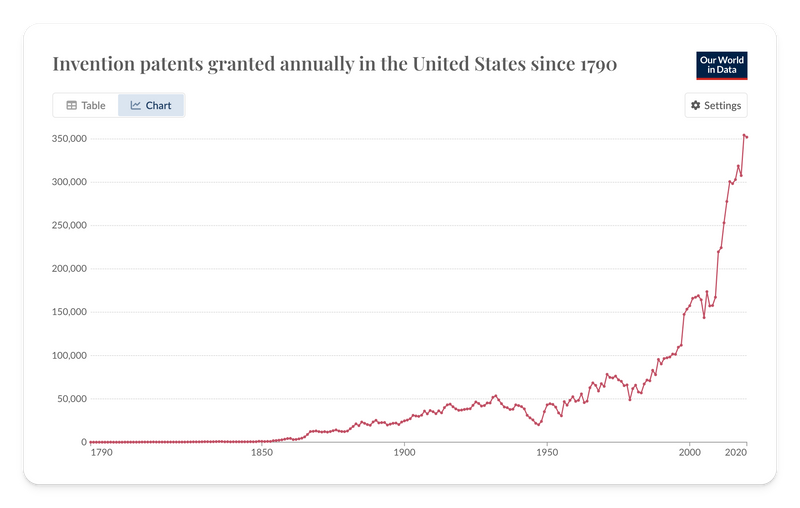

Look at this hockey stick graph of how many patents have been awarded each year in the US:

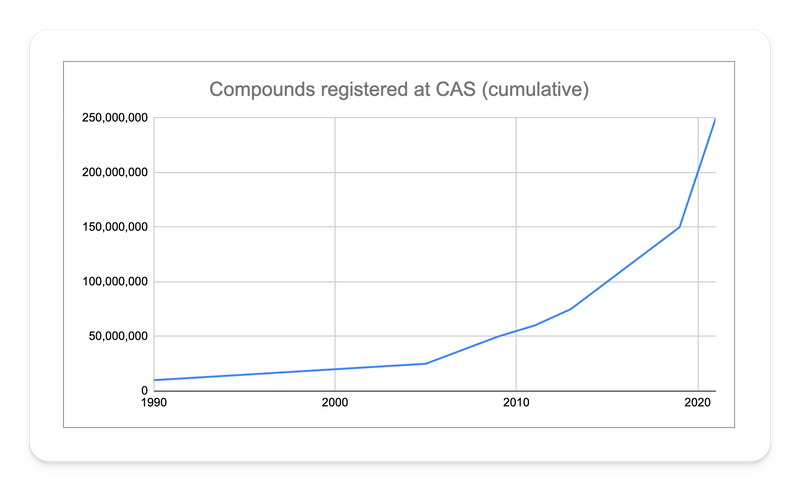

Or check out the Chemical Abstracts Service Registry, which logs all chemical compounds created or identified (another hockey stick!):

We’re making progress! Every year, we create new and wonderful things.

But: we also get things wrong sometimes along the way. (And we usually don’t find out for awhile.)

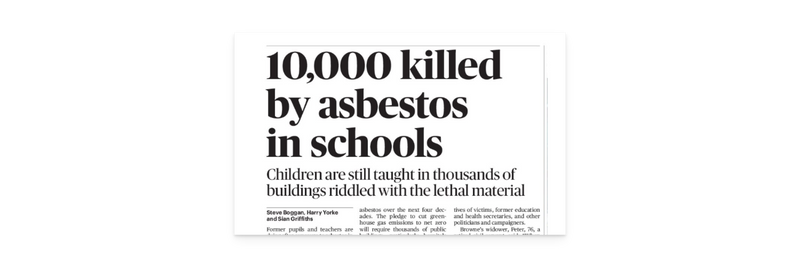

For example: asbestos was the best answer we’d ever found for fireproofing buildings.

But it turned out to cause mesothelioma, a deadly cancer.

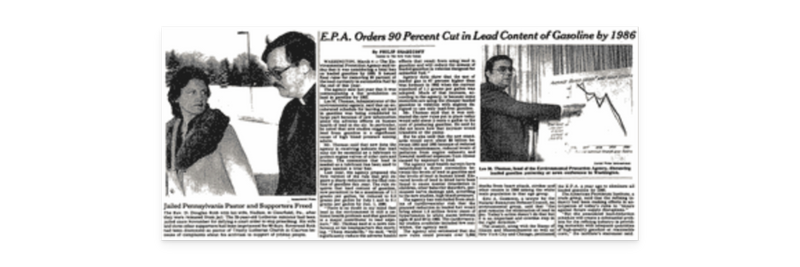

Leaded gas was more efficient than any vehicle fuel we’d developed.

But it crippled cognitive development in children.

BPA — Bisphenol A — is exceptional for making useful plastic products.

But it turned out to be an endocrine disrupter, creating negative impacts of which we are still understanding the magnitude.

Hexachlorophene was a great antibacterial and disinfectant.

But it killed children and caused brain damage before being pulled off the market.

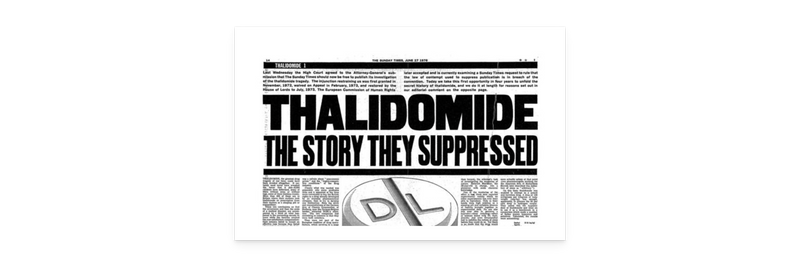

Thalidomide was a miracle drug for morning sickness.

But it caused birth defects and death in children whose mothers took it.

Technology is a double-edged sword — just about anything with new capabilities can be good or evil.

But sometimes one edge is sharper than the other.

In some cases the winning side is clear cut (internet: good; Thalidomide: bad). But sometimes it’s less obvious (DDT?).

And in many cases, we don’t find out about the problems until much later (BPA).

Here’s the root of the Toxic Progress Paradox:

Some percentage of new compounds and technologies will turn out to be bad, and as the pace of progress accelerates, so too will the raw number of bad outcomes from that progress.

Said another way: if we commercialize 10,000 new compounds or technologies in a year, we’re much more likely to create some bad outcomes than if we only brought 100 to market. And we are indeed creating more every year, so along with all the benefits that brings, we’re also very likely increasing negative impacts.

The Toxic Progress Paradox itself:

For the long-term benefit of humanity, we want the fastest progress possible; but, along the way, we also want as few bad outcomes as possible.

Does that mean we should stop developing new things? Or “pause” until we can get that error rate to zero? No!

So what do we do? How do we cut the knot of the paradox?

Most important: on a individual level, we need to take personal responsibility for our own decisions. We shouldn’t assume that “it’s all fine” — history shows us that it often isn’t.

That means being intentional about when we embrace new exposures of any type — technological, chemical, or otherwise. We should make our own individual tradeoffs based on our risk appetite, how much the new thing benefits us, and the information available to us.

Sometimes this is easy, sometimes it’s hard. But it’s worthwhile.

When I talk about this Toxic Progress Paradox, most people immediately jump to the big-picture view: that we should (of course) be seeking to minimize the “error rate” of new technology.

They jump right into (reasonable!) debate about the best mechanisms to accomplish this. Is the answer market mechanisms, holding people and companies responsible — and liable — when they create one of those errors?Cue Munger: “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome” (although does anyone have a citation for that quote?). Is it regulatory agencies? Something else?

They begin to ask: how much progress — if any — should we be willing to sacrifice to minimize that error rate? How free should the markets be? How constrained or unconstrained should the regulatory environment be?

And while those questions are undoubtedly important (and ones on which I have an opinion as well), I don’t think they are the right place to go first. I believe the most important takeaway from this paradox is the individual one, outlined above:

We need to take personal responsibility for our own decisions. We shouldn’t assume that “it’s all fine” — history shows us that it often isn’t.

That means being intentional about when we embrace new exposures of any type — technological, chemical, or otherwise. We should make our own individual tradeoffs based on our risk appetite, how much the new thing benefits us, and the information available to us.

It’s easy to get caught up in outrage about how things work in the world (and how they don’t). But if you spend all your time thinking about how to solve that problem, you’ll miss the one right in front of you: your own life.

Beware the Toxic Progress Paradox, and — as you’ve heard before — put your oxygen mask on before assisting others.

Looking for more to read?

Want to hear about new essays? Subscribe to my roughly-monthly newsletter recapping my recent writing and things I'm enjoying:

And I'd love to hear from you directly: andy@andybromberg.com