Jizo, Instax, and Impermanence

Jizo is a bodhisattva — a Buddhist saint-like figure who delays their final ascendance in order to help those on Earth. He protects children, women, and travelers, and his statues are often found on the side of roads or trails.

In Miyazaki’s “My Neighbor Totoro,” Mei finds refuge next to statues of Jizo when she gets lostI love Miyazaki’s art, hence using illustrations inspired by him since I started blogging again in 2024… but this is a real screengrab..

My wife and I like Jizo. In fact, we have a little Jizo statue outside at our house. We don’t have any other Buddhist iconography or even any other statues like it. I touch his head and smile every time I get out of the sauna.

In early 2024, we went to Japan for a week. My wife picked out a ryokan for us to go to for two days: which turned out to be in Nikko, a small city in the Tochigi Prefecture north of Tokyo. We knew nothing about the place other than the inn itself (which was remarkable).

On the bullet train up to Nikko, we started looking at maps and learning about the town. We found out that it has a famous Shinto shrine from the 17th century, built to honor the founding shogun of the Edo Period. And then, as we scrolled around Google Maps, we saw this:

The word “Abyss” caught my eye, and then, Jizo.

“I wonder if that’s the same Jizo?”

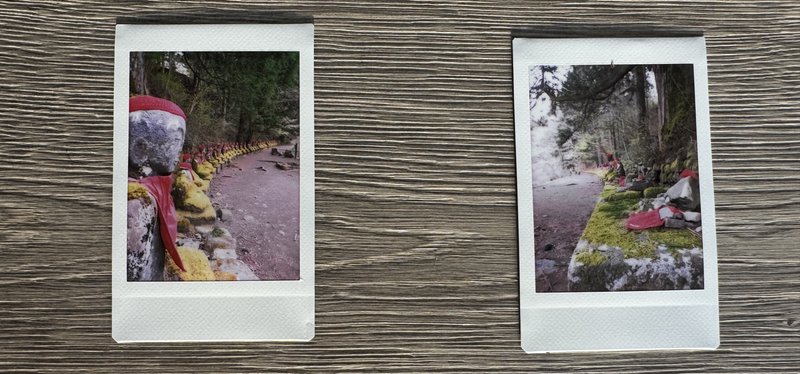

It was. It turns out that Nikko is home to a famed set of Jizo statues. Within the Kanmangafuchi Abyss — a gorge carved out by Mt. Nantai’s eruption about 7,000 years ago — dozens and dozens of Jizos stretch out in a line, each wearing a signature red knitted cap.

They were carved in the late 1500s and early 1600s. The flood of 1902 wiped a number of them out, and the remainder are in various states of disintegration. Some are fully composed, and others are little more than a pile of pebbles — but each still with a knitted red cap.

We knew we had to go.

I love taking photos on a Instax cameras. They of course have a special aesthetic, but there’s also something more meaningful: the nature of the camera immediately printing out a photo means you can’t try to get the “perfect” shot. You take your picture, and then you have to wait a couple minutes to see the result. By then, you’ve usually moved on or the scene has changed.

In a world of digital and phone cameras, where people shoot, review, and repeat until they get it just right… there’s something freeing about the Instax.

We had forgotten ours back in the US, but thankfully, Japan is the home of Fujifilm, the creators of Instax cameras. So we stopped in a couple Tokyo neon-light electronics stores earlier in the trip to get one.

My wife convinced me to try something different — instead of a traditional Instax, we’d get a digital/analog combination one. When you take photos, it doesn’t print them immediately. They get saved, and then you review them later on the viewfinder and choose which to print.

I didn’t love the idea. It flew in the face of why I told myself I enjoyed Instax photography. But she convinced me, and over the coming days in Tokyo, I realized how right she was. I still didn’t feel the pressure to take the perfect shot, and I no longer wasted film on bad photos. And, without her convincing me, I wouldn’t ever have this story and lesson to write.

We had great fun with the Instax. And, in homage to being in the country of its creation, we left the interface language set to Japanese. So we muddled through the menus based on icons and intuition.

On our first morning in Nikko, we went for a walk to the Kanmangafuchi Abyss. I took the Instax and snapped photos along the way, phones firmly stowed away.

We finally came upon the Jizo statues, and they were marvelous. Legend says that it’s impossible to count how many there are — that they disappear and reappear, causing travelers to lose track of how many they’ve seen.

I took photos of the arc of Jizos bending away from us; photos of individual Jizos that caught my eye; photos of the beautiful abyss beside us. I didn’t print any — I’d save that for later, as I had been.

Towards the end of the hike, I got a warning (in Japanese) on the Instax. It seemed like — perhaps? — it was out of memory. So I navigated clumsily through menus I couldn’t read, trying to figure out how to delete some of the less compelling photos on the reel.

I got there eventually, found a photo I didn’t love, and then hit the trash icon. A spinner came up on the Instax screen, and spun for quite awhile — long enough that I wondered what was happening.

And then, suddenly, I was faced with the same screen as when I first got the camera: a screen presumably saying there were no photos on the device. They were all gone.

I stared, shocked. I had just framed up and taken so many incredible photos, capturing memories and art both on the hike and in the day before. I hadn’t printed them. And then I wiped them all away. I wasn’t happy.

On that trip, I had been re-reading the Seeing that Frees, by the remarkable, late Dharma teacher Rob Burbea. I came back to it because of other Buddhist readings I was muddling through — I wanted to return to Burbea’s clear lens on the ideas.

I don’t consider myself a Buddhist but have found many of the practice’s ideas to be helpful, and my biggest conceptual challenge at that moment was impermanence.

In some sense, the Dharmic path is one of progressively ceasing to grasp or cling. We fabricate the perceived reality around us by clinging to identities, definitions, norms, and ways of looking. These things — and all else — are fundamentally devoid of inherent essence or meaning. They are created by our perception of them (and yes — the term “our” can imply an “I,” and that too is fabricated).

A powerful tool in this releasing of grasping — the cessation of clinging — is a recognition of impermanence. The Buddha taught that all things are impermanent, and, in a sense, that understanding alone is sufficient for us to be relieved of the grasping. For if you truly know that all things disappear (if they were ever there in the first place), you can then relax your grip on them.

Realizing that your child will one day not be a child but an adult gives you the expansiveness to recognize that you won’t always be able to control them — and so do you need to cling to controlling them now?

Realizing that your self-identification with your job will one day disappear and change — for your job and life will change — gives you the peace to loosen your tight grip on that self-identification.

Or, realizing that the photos you took and prized… that those photos will disappear… and in fact, even if they hadn’t been deleted… they would have faded in your consciousness quickly… and eventually entirely…

That gives one the sense that perhaps the clinging pride and attachment that came with those photos was not so warranted — and ultimately only served to bring about suffering.

Sitting by the long line of Jizos — some now nothing more than a couple stones with a small cap — gazing at a shrine on the edge of the abyss, holding a camera with a “no photos” icon indifferently displayed — I felt the lesson in impermanence I had been reading about.

In hindsight, to have unknowingly clung to pride in something so impermanent (or to anything, really) was a trap. It guaranteed suffering as the object inevitably winked out of my perception of the world. The Jizos and the Instax taught their lesson well.

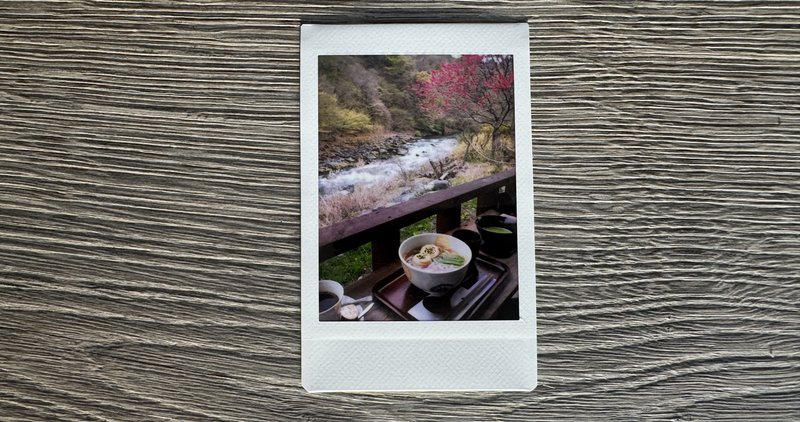

(But yes, I still took more photos on the walk back — several included in this post. We recommend stopping at Santenamataro for a bowl of that Yuba Udon on your way. The shopkeeper is wonderfully kind.)

Looking for more to read?

Want to hear about new essays? Subscribe to my roughly-monthly newsletter recapping my recent writing and things I'm enjoying:

And I'd love to hear from you directly: andy@andybromberg.com