Stanford Lecture on Theory of Constraints for AI

Earlier this month I gave a guest lecture at Stanford’s CS 224G course “Building & Scaling LLM Applications” on applying the Theory of Constraints to building LLM products. Thanks to instructors John Whaley and Jan Jannick for inviting me! Below are the slides from the talk with accompanying notes.

The Problem

It’s never been easier to build things with LLMs. Anyone can spin up a prototype in an afternoon. But getting from prototype to a good product – one that works reliably, consistently, at quality – is a different challenge entirely.

The big challenge (and arguably, the magic) with building on LLMs is that they are non-deterministic. Ask the same question twice and you get different responses. For a simple factual query that’s fine – both answers above are correct. But when you’re building a product, this variance becomes a real problem.

And complexity compounds non-determinism. Especially when you chain LLM calls together or admit arbitrary user input, each non-deterministic step multiplies the variance of the next. By the end of a meaningful AI pipeline, things can shoot far off in the wrong direction.

This compounding non-determinism causes quality and reliability issues. You can’t always just “vibe” your way to a good product when the output surface is this wide. Enter: systems thinking.

The Theory of Constraints

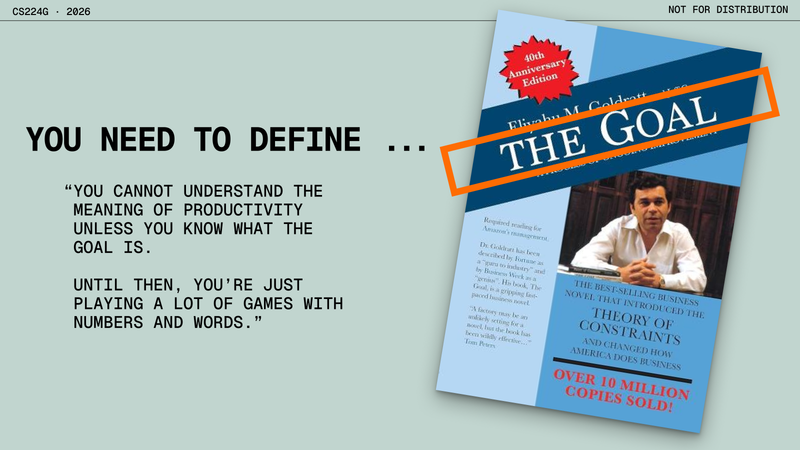

One framework I’ve found very useful for this is the Theory of Constraints (TOC), introduced by Eliyahu Goldratt in his 1984 book The Goal. Yes, it’s a 1980s sales-y looking book about factory management. Bear with me.

(I’ve written about TOC before: Theory of Constraints overview and Applying constraints thinking to AI.)

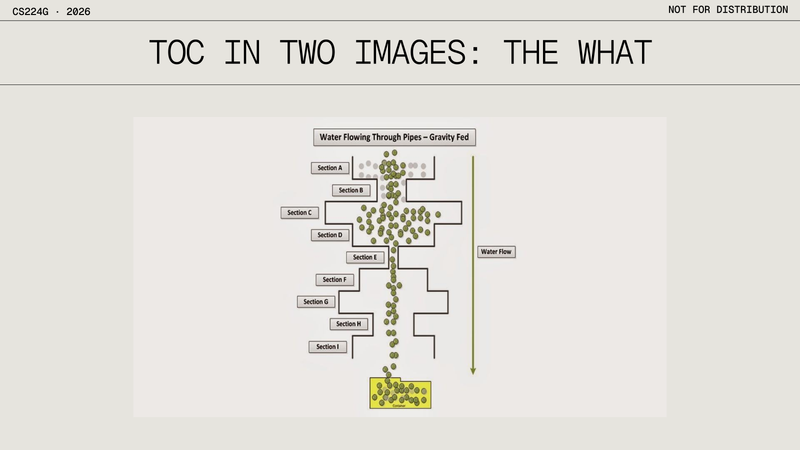

TOC in one image: The What. Think of a system as water flowing through a series of pipes. Each pipe section has a different diameter. The total throughput of the system is determined by the narrowest pipe – the bottleneck, or “constraint.” No matter how much you widen other sections, total flow doesn’t increase until you address the bottleneck.

This is one of the core principles of ToC, and it applies broadly. There is almost always one rate-limiting step that is constraining your system. You could improve any other part of the system and it would do nothing.

And note here that “throughput” is meant generally. It can refer to speed, or quality, or any other metric you are measuring. But regardless, in the “pipeline” to “throughput,” there will be one constraint.

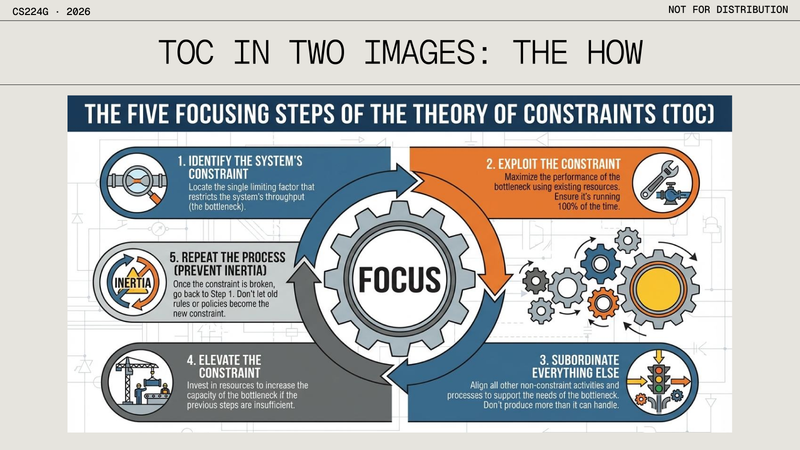

TOC in a second image: The How. Goldratt’s five focusing steps:

- Identify the system’s constraint (the bottleneck)

- Exploit the constraint (maximize its performance by leveraging existing resources)

- Subordinate everything else (align all other processes to support the bottleneck)

- Elevate the constraint (invest to increase the bottleneck’s capacity)

- Repeat (prevent inertia – go back to step 1)

If you just do these over and over again, you will fix your problem.

Modeling the LLM System

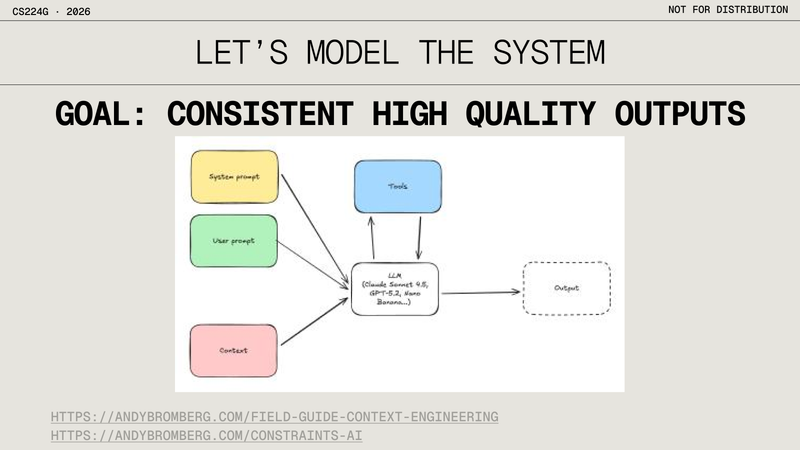

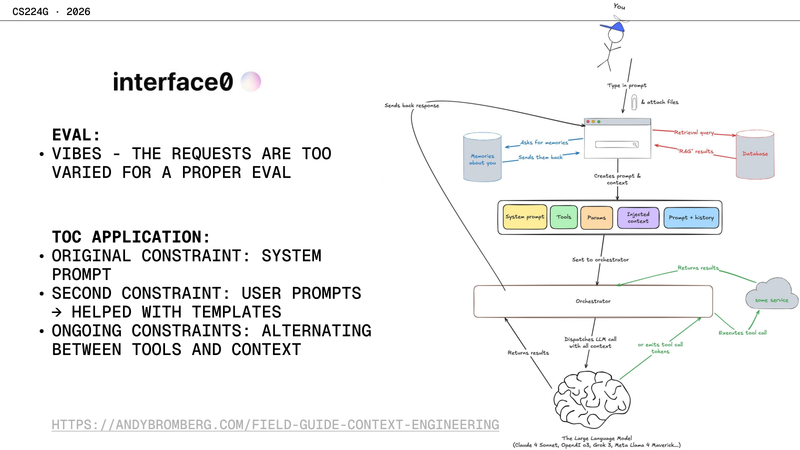

To apply TOC, you first need to model and understand the system you are optimizing and define its goal. An LLM application has a few core components: the system prompt, the user prompt, the context (retrieved data, files, etc.), the tools available to the model, the LLM itself, and the output.

I’ve written about this in my field guide to context engineering and in theory of constraints for AI.

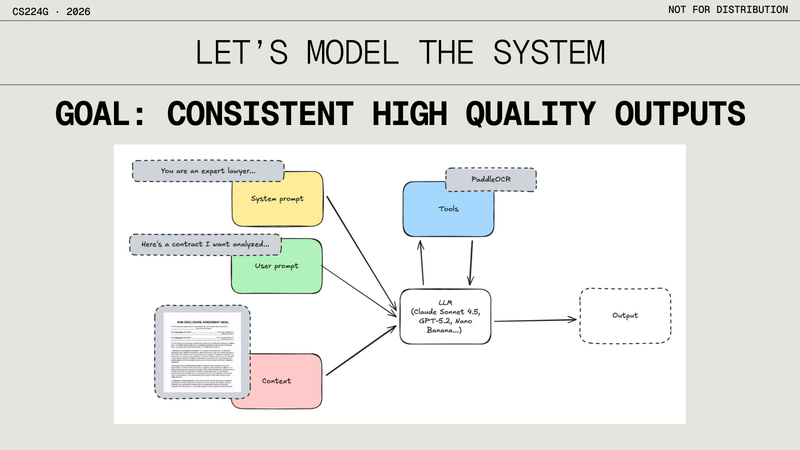

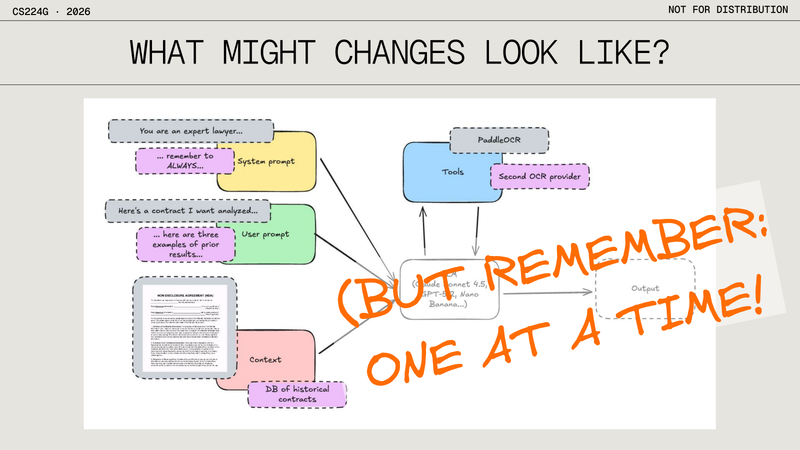

Here’s what that looks like concretely. Imagine you’re building a contract analysis tool: the system prompt says “You are an expert lawyer…”, the user prompt includes the analysis request, the context includes the actual contract document, and a tool like PaddleOCR handles document extraction.

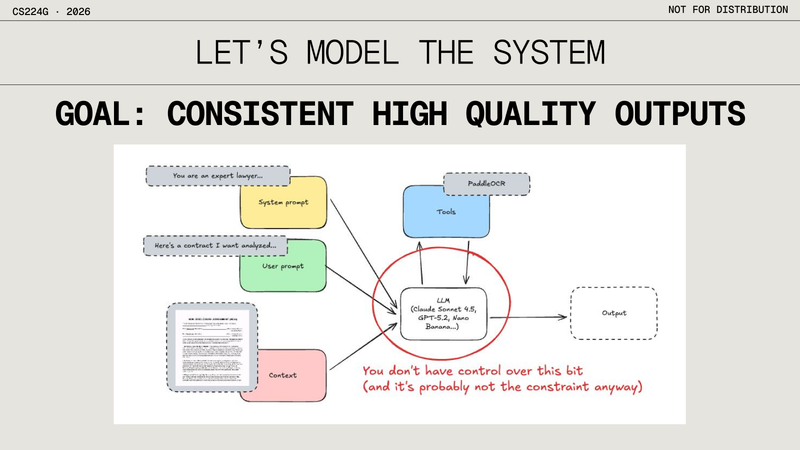

One thing to note: you don’t have control over the LLM itself. You can’t change how Claude or GPT work internally. And honestly, the model is probably not your bottleneck anyway. The frontier models are remarkably capable today.

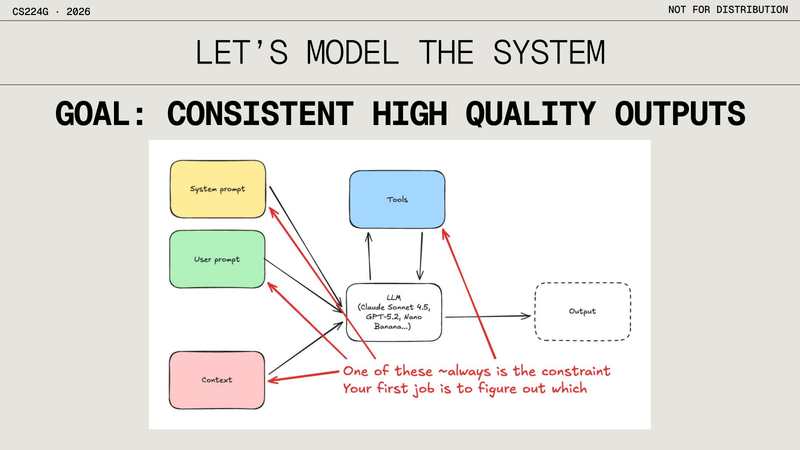

What you do have control over are the inputs: the system prompt, user prompt, context, and tools. One of these is almost always the constraint. Your first job is to figure out which one.

Once you’ve identified the constraint, you can start improving it – adding detail to the system prompt, providing few-shot examples in the user prompt, enriching the context with a database of historical documents, adding a second OCR provider for redundancy. But remember: one at a time. This is key to the TOC approach. Change one variable, measure the impact, then reassess.

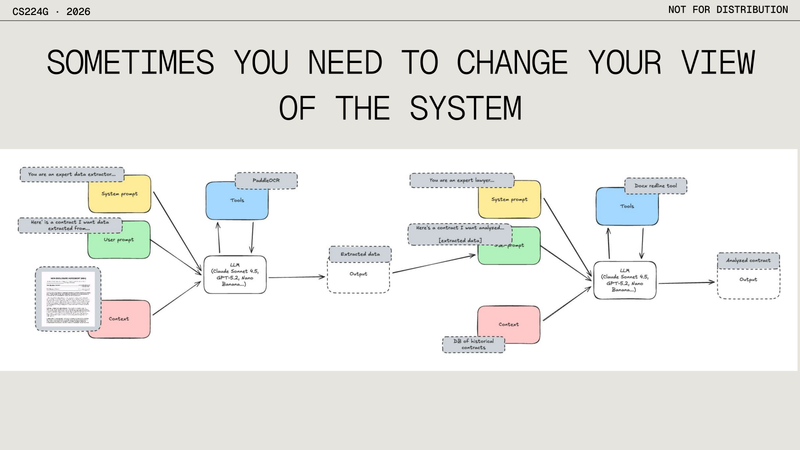

Sometimes the constraint isn’t a single component but the system architecture itself. In that case, you need to change your view of the system. For instance, splitting a single LLM call into a two-stage pipeline – one for data extraction, another for analysis – can dramatically improve results by giving each stage a focused task, better tools, and cleaner context.

Defining the Goal and Measuring Progress

You need to define The Goal. As Goldratt puts it: “You cannot understand the meaning of productivity unless you know what the goal is. Until then, you’re just playing a lot of games with numbers and words.”

The chain of reasoning:

- Good results need improvement

- Improvement needs evals

- Evals need a goal

- A goal needs a definition

Start at the bottom: define what “good” means for your product, concretely and specifically.

We said our goal is consistent high quality outputs. But how do you actually measure that? We need to in order to apply the Theory of Constraints and see if we’re improving or not.

Evals

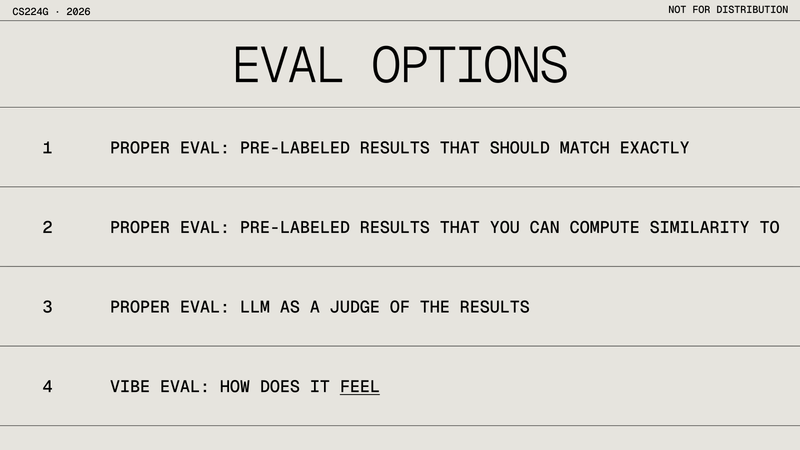

In the AI world, ways of measuring against a goal are called “evals.” In my view, there are categorically two approaches:

- “Proper” evals – structured, automated evaluation with scored results. (It is much easier to build a good product if you can create these!)

- Vibe evals – a gut-check approach.

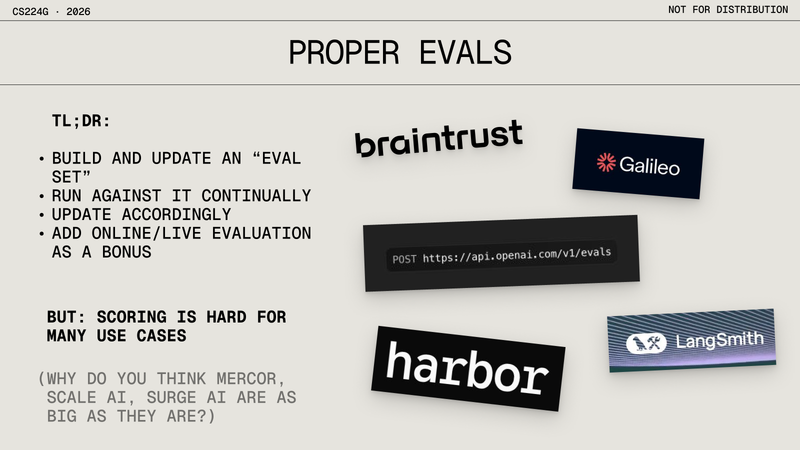

For proper evals: in general, you want to build and maintain an “eval set” of test cases, run your system against it continually, and update accordingly.

(If you’ve wondered by Mercor, Scale AI, and Surge AI are as big as they are… it’s because of this. They are providing evals to every major AI lab and application company. It’s big business.)

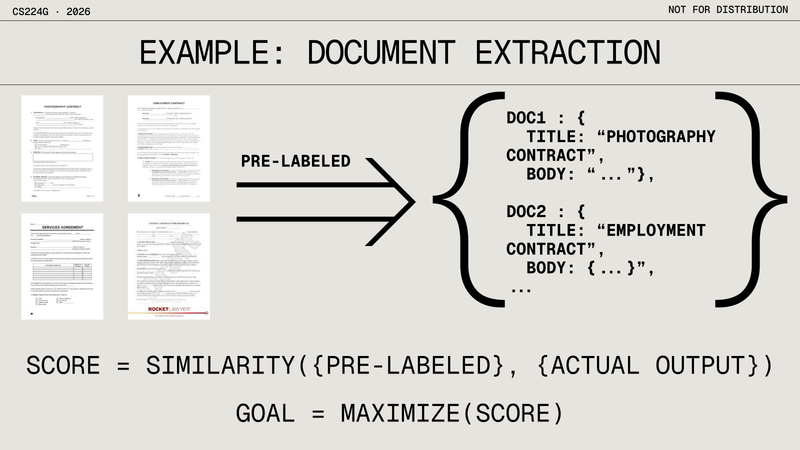

Here’s a concrete example: document extraction. You have pre-labeled documents with known-good structured output. You run your system on the same inputs, compute similarity between the expected and actual output, and try to maximize that score. This is the dream scenario for proper evals.

For vibe evals: sometimes your product’s outputs are too varied or subjective for structured scoring. In those cases, you just… look at the results and ask yourself how good they are. Not as good, but much easier.

The full spectrum of eval options:

- Proper eval: pre-labeled results that should match exactly

- Proper eval: pre-labeled results you can compute similarity to

- Proper eval: LLM-as-a-judge of the results (this is a very common approach right now)

- Vibe eval: how does it feel?

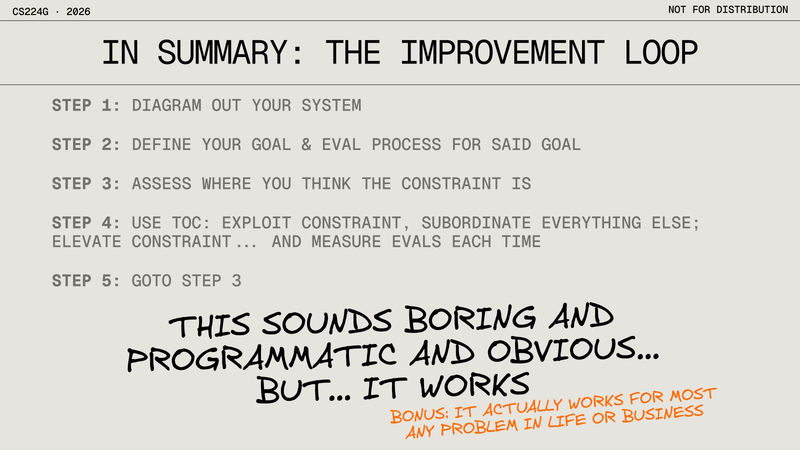

Putting it all together into a repeatable improvement loop:

- Diagram out your system (map the components and how they connect)

- Define your goal & eval process (proper or vibe evals)

- Assess where the constraint is (system prompt, user prompt, context, tools, or the system view itself)

- Use TOC: exploit the constraint, subordinate everything else, elevate the constraint… and measure evals each time

- Go to step 3

This sounds boring and programmatic and obvious… but it works and is what powers the most impressive/magical AI applications. And most people do not approach it so rigorously.

(Bonus: it actually works for most any problem in life or business. Not just AI!)

Practical Examples

Three practical examples of applying this framework:

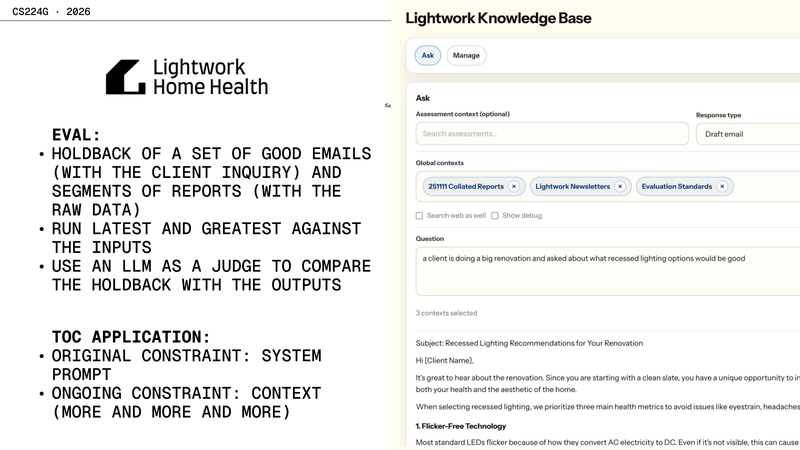

1. Lightwork Knowledge Base

Lightwork Home Health built a knowledge base tool where our team can ask questions and get draft email responses or segments of reports grounded in prior research and reports.

Eval approach: holdback a set of known-good emails (with the client inquiry) and segments of reports (with the raw data). Run the latest system against these inputs. Use an LLM as a judge to compare the holdback with the actual outputs.

TOC application: the original constraint was the system prompt. After improving that, the ongoing constraint has been context – needing more and better source material.

2. interface0

interface0 is an AI interface for power users and teams. Because user requests are so varied (and it is sub-scale), proper evals aren’t feasible here – it’s pure vibe evals.

TOC application: the original constraint was the system prompt. The second constraint was user prompts, which was addressed by adding templates. The ongoing constraints alternate between tools and context.

3. [Redacted]

A large enterprise AI implementation (details redacted for confidentiality).

Eval approach: expert feedback on results (some structured, some unstructured) combined with user feedback (unstructured).

TOC application: the original constraint was system prompts for specific subagents. Then it moved to tools. Now it’s back to context and system prompts. The constraint keeps moving – which is exactly what should happen.

A Key Takeaway

The state of play today: the LLM is ~never the constraint. The frontier models are good enough to do just about anything. If we buy the Theory of Constraints and the idea there is a constraint in the first place bottlenecking quality, that means there are things in your control to get your product to the quality and consistency you want.

It is your job to map the system, build evals, find the current constraint, and fix it. Rinse and repeat.

Bonus: Tools I Can’t Live Without

A snapshot of the tools I was finding most useful as of February 2026 (probably already out of date by the time you read this).

- File Search API in Gemini is great for quickly prototyping RAG applications — I don’t think there’s a faster way to get a good RAG pipeline up and running for something like the Lightwork knowledge base

- Trigger.dev is amazing for long-running agentic pipelines and durable execution. Great developer experience.

- Braintrust.dev for automated eval pipelines and observability

- TextGrad is a very cool library from the Zou Group at Stanford for a sort of “backprop” of text gradients

- Claude Agent SDK is my favorite harness for building agentic applications

- Compound Engineering from Every is a great starting place for planning and building workflows inside of agentic code assistants. Instant level up on productivity if you aren’t using something similar already.

If you have questions or want to discuss any of this, feel free to reach out: andy@andybromberg.com.

Looking for more to read?

Want to hear about new essays? Subscribe to my roughly-monthly newsletter recapping my recent writing and things I'm enjoying:

And I'd love to hear from you directly: andy@andybromberg.com